Last week, I had the opportunity to visit the Memorial Art Gallery (MAG) in Rochester (New York). Despite being a current junior - and a studio art major - at the University of Rochester, this was my first visit to the gallery, which is a public art museum that also happens to be owned by the University. The gallery holds a permanent collection with 50 years worth of world art. In addition, there are two exhibits that are currently on view, both of which I recommend; they are: Art for the People: Carl W. Peters and the Rochester WPA Murals, and Jacob Lawrence: The Legend of John Brown Portfolio. The museum is open on Wednesday through Sunday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on Thursdays from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m., as there are MAG Art Socials at night. As a gift from local art patron Emily Sibley Watson in memorial to her son, admission to the MAG is FREE to all University of Rochester students. It is one of few university-affiliated museums in the country. I highly suggest that you head into downtown Rochester and experience the art for yourself. Exploring the gallery will take you through 5,000+ years of art history. I visited for an art class with the express purpose of viewing two particular paintings: Interlude, 1963 by John Koch, and Three Jujins, 1995 by Hung Liu. Below, I’d like to share with you my experience in the gallery and my response to the painting.

First, the experience:

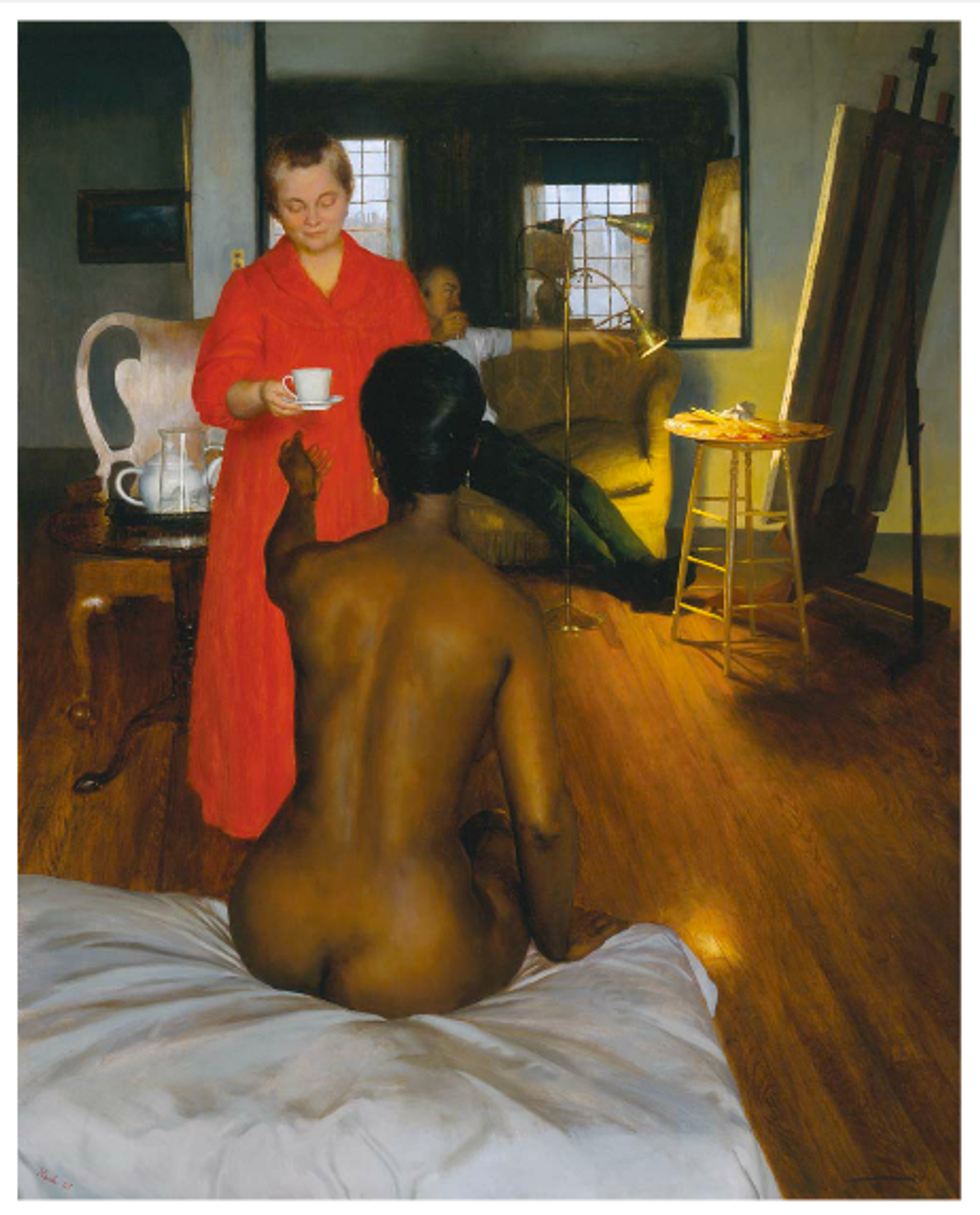

I enter the Memorial Art Gallery, lost in search of the two paintings for my class assignment. The receptionist presents me with a map and pinpoints the exact locations of the two works with red ink. I venture into the halls of the gallery, scouring the walls, looking for what the woman described, as well as trying to recall my prior knowledge of the images. I find both, but I find myself unfathomably astruck by John Koch’s Interlude, and thus, I return to his painting. Crouching beneath the frame, I type the tombstone into a new Word document, my calves burning. I scan the masterpiece up close, looking carefully at both the brush strokes and a discernable technique in painting and in blending of the colors. My focus is drawn to the woman of color at the forefront of the work, her nude body so delicately painted. Every shade of her skin, every muscle in her back, and every curve of her body is given great attention by the painter. Other museum-goers pass by me, and I inch my way back into the adjacent gallery to place myself on a couch parallel to the painting. This is a full front-on view, but from afar. From here, I can see the white bed sheets that caress the black woman’s posterior. Her body is eloquently painted with a lighting technique that emphasizes the strength in her physical structure. The vibrancy of the older white woman’s red robe captures my attention and juxtaposes the natural colors present in the rest of the painting. Lighting in the background is strategically placed in order to highlight the easel, as well as the canvas in progress. Koch is skillful in his composition, technique, and overall meaning, the last of which I will be discuss in more depth below.

Up close, the parts of the painting that glisten in the light are the black woman’s jet black hair, parts of the older woman’s red robe, and areas in the window pane. The realistic representations of the people, the interior of the room, and the objects inside of it make it feel as if I am in the room with them. I am present, and experiencing the emotions, the light glimmering on the mahogany floors, or even being offered tea like the black woman who is sitting on the bed. The viewers too, are invited in as guests, and treated as such. We are given a glimpse of the New York house and the luxuries it entails: the hardwood flooring, expensive furniture, delicate China, and lighting fixtures. At first glance, the windows appear to be behind the lounging artist, but I then realize it is actually the reflection of the room behind the model that I see. We are in the room with them, and suddenly, our view-finder is cropped, and we are in the Memorial Art Gallery instead of Manhattan.

It is important to understand the meaning or underlying story of this particular work of art, because at first glance and with a lack of information about the artist, there can be several possible interpretations. First, the forefront is a black woman; she is nude and her back is towards us; thus, we cannot see her face, and her identity is unknown. Her outstretched arm moves towards a cup of tea being held by a white woman. This can lead one to comment on the social norms prevalent in 1960s New York. From previous art history courses I have taken, I know that the decade of “The 60s”, particularly in major cities in the United States, is notably an era of counter-culture, a time in which the Western world began to reject all that was previously known or expected in favor of new and very different ideas about just about everything. This social revolution was in direct response to the conservatism and conformity experienced in the 1950s. In a continuation of the Civil Rights Movement that started in the mid-50s, the 60s held movements for Black Power and giving African-Americans voting rights as well as freedom from generations of racial discrimination. There were acts of civil disobedience, with notable examples including but not limited to the Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama, the Marches on Selma and Washington, and leaders like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. There was turmoil between generations, as some could not forget slavery - or forgive it - and some people in the country either did not want to grant civil freedoms to blacks or still walked around with a “blind eye,” which is equally blameworthy.

Another possibility of interpretation of Interlude is that the white woman depicted in the painting is a servant within the Koch household. But in reading the wall label for Lopate’s, John Koch: Painting a New York Life, I found out that the white-haired elder woman is, in fact Dora, Koch’s wife, and the black woman on the bed is a model. Thus, the painting is in fact a reversal of social norms; it actually depicts a white woman serving a black woman rather than the expected other way around. As my title denotes, this simple and kind gesture from the artist’s wife is uncommon at the time, especially given the historical context of the work. Prior to the date of this painting, many African-Americans migrated from the South to the North to improve their lives, and based on this particular painting, it may be inferred that modeling may have been a way that they found work and a way to live. Koch is known for painting his own life, his apartments and their interiors, and his furniture; he composed his paintings in such a way so as to resemble still lifes, making them at once realistic but also staged. His paintings, and his work Interlude in particular, portray an upper class life that comments on the social and economic disparity between the classes, a theme that he started in his early career by painting portraits of prominent New Yorkers.

Personally, I find this piece very intriguing because I previously took a course titled, “Art & Identity: Ways of Seeing,” (which focused on discussions of American art and American identity) and because my boyfriend is half white and half African-American. John Koch said, “I am quite visibly a realist, occupied essentially with human beings, the environments they create, and their relationships.” The realistic qualities of Interlude are visually striking, and the relationship between the physical space in Koch’s apartment and the interactions between the people depicted in the work may provoke a discussion of race, ethnicity and social relations. Some of my anthropology courses here at U of R have taught me that race is a socially constructed idea; then, so, too, must be inter-racial interactions. I wonder what Koch’s perspective on these differences would be, as his painting leaves room only for interpretation, and not answers. He seems to be approving of his wife being very welcoming and caring towards the black model. Yet some white people at the time of this painting would have been appalled at the thought of a person of another race being a guest in their home, let alone speaking with them or, worse yet, having someone of their own race wait on them.

Today, the percentage of interracial relationships in the United States - and in the rest of the world - has increased greatly over previous generations, mine being among them, but I believe that the questions prompted by this painting are still prevalent today. African-Americans are still living in poverty when compared to whites. There are still many people - of many races - who do not believe in interracial relationships. Sometimes, I feel as if there are some people who judge me simply because I have a boyfriend who is part black, but at the same time, I also feel like there are other people who respect me for the same reason. I attended an inner city public high school, I had friends from many different neighborhoods, socio-economic classes, countries, and cultures, yet there were times when I felt that people who had less money, or who had a different skin tone were more respectful of me than those within my own phenotype. The action depicted in this painting is the act of passing a cup of tea to another person who is a guest in a home. To me, this action is a polite and respectful thing to offer as a guest enters or enjoys your home. The keywords there are guest and home. Typically, before the civil rights movement of the 1960s, African-Americans were regarded mostly as servants within the homes of white people, not as equals; nor were they invited in as guests, but rather, they were told to come in and only to perform servile tasks. Koch’s ingenuity and skill in composition are among the best among artists whose works I have studied to date, and in Interlude, the work lends itself towards a discussion of people, race, environments, and relationships of all types, including inter-racial ones. In viewing this piece in the Memorial Art Gallery, I felt drawn to its presence, as it provokes thoughts and discussions that I believe are important both in art and in social relations.

I encourage you to go to the MAG and visit this painting in person. Afterwards, feel free to reach out to me and give me your thoughts - about the painting and the questions it might elicit. My hope is that this article will bring needed attention to a very talented artist, appreciation for the MAG, and intellectual discussions about art, race, and culture. I would love to hear from you! Enjoy!