I just finished my junior year in college, entering the final stretch of my college career. I'm shocked that I got this far never questioning my major... until now.

I've been a psychology major for what seems like forever. I was inspired by my senior year high school teacher who taught Introduction to Psychology and I fell in love with it. I knew then and there that psychology was what I wanted to do with my life. I've always considered myself to be a good listener, and I loved being able to give people advice if they needed help. My parents raised me to always put myself in the shoes of others, and that upbringing sparked my natural curiosity to finding out how others' walks of life affect their mental wellness.

When I came into college, I struggled with the psychology courses. A misconception about psychology that I fell for was Introduction to Psychology is not at all how "real" psychology courses are. Introduction to Psychology focuses on giving you the basics and giving you an overview of many different concentrations, which I thought were incredibly interesting at the time. As I fell deeper in psychology courses in college, I realized that psychology is hugely focused on clinical, statistical, and research-based methodology - none of which are interesting to me in the slightest.

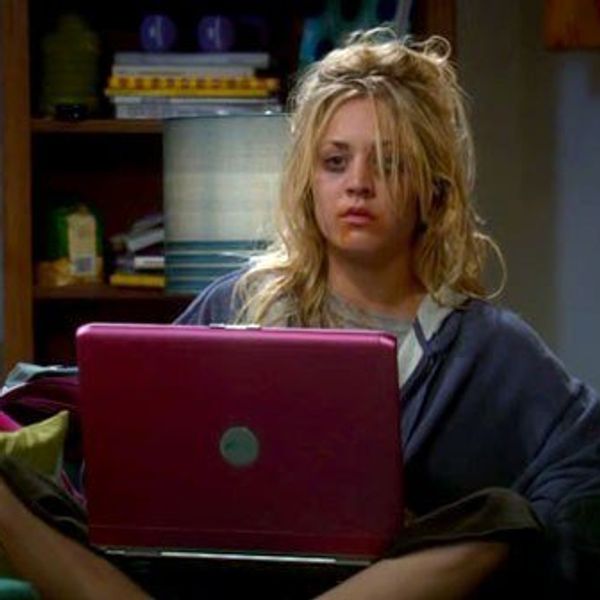

In my courses, I never did exceptionally well in them unless they were of the utmost-fascinating to me, being content with less than an A. Most concepts became boring to me, and I didn't feel myself caring about anything that psychology had been. I knew I didn't care about this anymore when I got my second C, because I shouldn't be getting C's in a major I thought I loved. My final straw was applying for a fifth-year program and getting denied because I didn't have a 3.67 cumulative GPA for the program. Going into my senior year, I have a 3.22 cumulative GPA while being heavily involved in extracurriculars, having a part-time job, and having a very impressive accumulation of community service hours, yet none of that made up for my .4 deficit.

This tug-of-war with myself made it so complicated for me to figure out my life path. I dismissed these thoughts before saying, "You already took too many classes in psychology, you'll never graduate if you switch now," and "It'll get better." However now, going into my senior year, I have no drive to stick with psychology. I want to switch my major.

As I thought more about this, I felt embarrassed and defeated. It's hard to come to terms with the fact that you spent all of these years and all of this money on something you thought you liked. Though psychology is one of the more diverse majors, I now have to accept that after graduation, I will need to start all over.

Because of this reality check, I decided to sit down and do some research, and I found out I was completely wrong. It's not me, it's the university.

In an article by Liz Freeman, from Butler University, Freeman explains that most students are not developmentally ready to make the right decisions on self-reflection, like choosing a major. To make these decisions, students must enter the developmental stage called "multiplicity." In this stage, a person is able to recognize that multiple options exist even when the right decision is unknown. First-year students are unable to recognize this stage, due to their lack of experience and lack of knowledge on their own personal goals, values, and interests. I believe this holds true in real life, as well. How many of us can look back and say we have the same goals, values, and interests are our 18-year old self? How many of us can say that we are still the same person as our freshman-year counterpart? How many of us have the same jobs, same friends, same hobbies as a few years ago? We are constantly changing and evolving, and changing majors should be no exception.

According to the University of La Verne, 50-70 percent of students change their majors at least once, most will change majors at least three times before they graduate. However, ULA says that more than 50 percent of college graduates pursue careers that are not related to their major and claim that most employers just want you to have a degree in something, that what you do in your graduate work will dictate how your career path will go.

Freeman pitches some solutions for colleges to mend this problem in her article, explaining that there are many programs Universities can implement to reduce the need to switch majors. Freeman would like Universities to keep with any first-year seminar programs they may have, but explains that colleges should implement career assessments for every student. She also says that colleges should veer away from naming majors with a "pre-" label, and instead switch to "undecided" and "exploratory" words to cut down on the negative connotations of indecisiveness. Freeman also hypothesizes that Universities and colleges should allow students to be undecided for up to two years, and she believes that would increase the amount of students who stay with their majors.

Though these solutions may not currently exist at your school, we need to challenge Universities to change their process on major selection. If 70 percent of students are changing their major at least once throughout their college experience, that's a huge problem and it's not allowing students to develop correctly into the career path they fit into to.