The gender pay gap. It exists! And it’s hella complicated.

The issue of women receiving less pay than men has moved towards center stage in recent years, and everyone has heard those familiar cries of “77 cents for every dollar a man makes!” and “Equal pay for equal work!” These catchy slogans simplify the problem, and leading us to believe that the solutions lie in legislation that combats gender discrimination in the workplace and in socializing women to assert themselves while negotiating salaries.

Unfortunately, these solutions are not enough. They only address a simplified, skewed version of the problem, not the cause of the problem itself.

(First, remember that the statistics are different for women of color. Second, let's remind ourselves that we're talking about differences in average earnings over a lifetime, not hourly wages.)

Claudia Goldin, a Harvard professor and economist, devoted much of her life’s work to studying the gender pay gap. In her 2014 essay, “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter,” she says this:

“Quite simply the gap exists because hours of work in many occupations are worth more when given at particular moments and when the hours are more continuous.”

Not what we expected, is it? And yet, when we look at the choices of women versus the choices of men in the same occupations, it kind of makes sense. And it makes one wonder about the reasons behind those choices… Could the answers to the gender pay gap be found in a feminist question that has been brewing for decades, right in front us?

It all boils down to temporal flexibility.

A common misconception about the pay gap is that its cause lies in the choice of occupation. The idea that women just happen to choose occupations that pay lower than those of men is part of what feeds various social campaigns to encourage young women to go into the STEM field. However, Goldin shows that the pay gap actually occurs within fields, not across them, stating that "what happens within each occupation is far more important than the occupations in which women wind up."

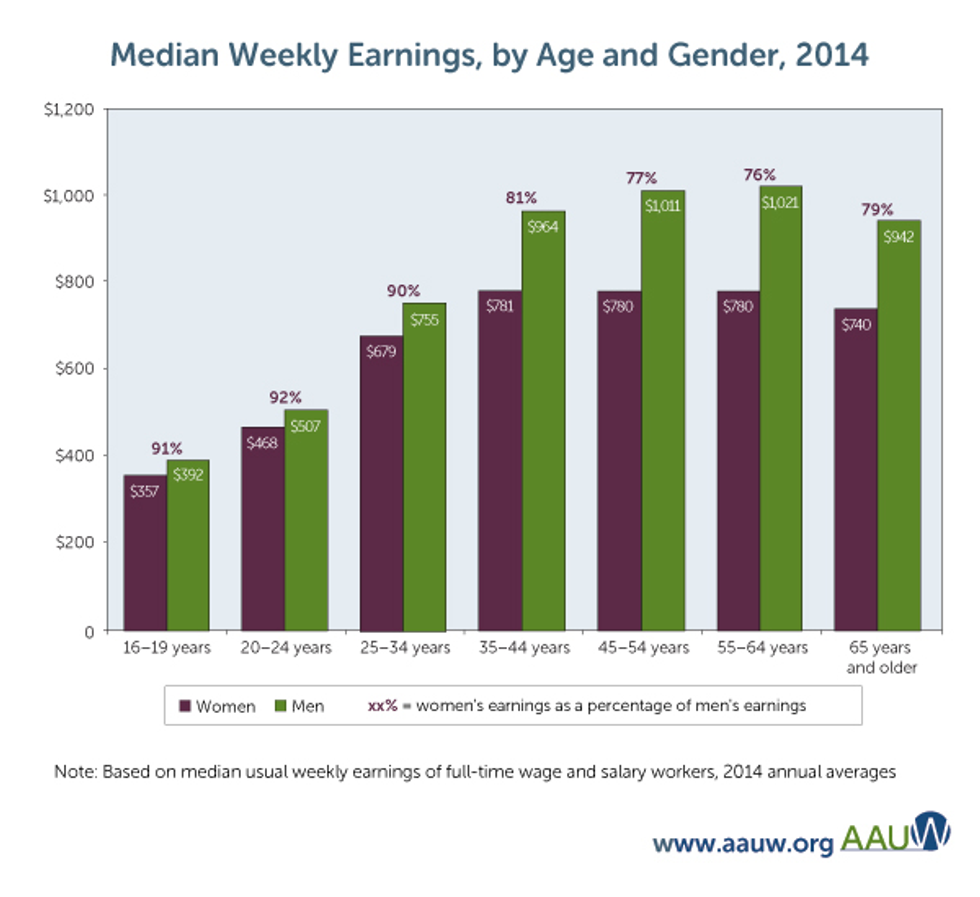

Further, she explains that the pay gap increases with age.

Why? According to Goldin, it’s simple: The point at which women start to earn significantly less than men is the point at which they become mothers. Once the average woman has her first child, she begins to slowly remove herself from the labor force little by little, and sometimes altogether, becoming a stay-at-home mom. This is most clearly illustrated by the fact that the pay gap between women without children and men (with or without children) is almost nonexistent.

This is why “temporal flexibility” is important: Women with children are more likely to work part-time, and more likely to request certain hours. The gap therefore arises from the penalty that these mothers take; after all, the less time you spend at work, the less you get paid, right?

It also boils down to “nonlinear” pay.

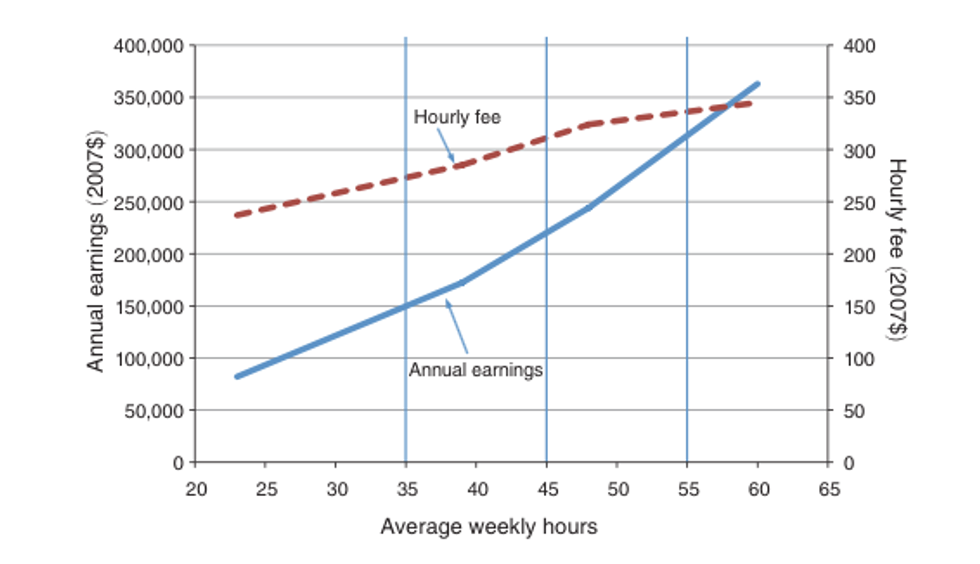

The professions with the largest gap in earnings are in the financial and business sectors. Interestingly enough, someone employed in these sectors who spends more time working receives earnings at a rate that is disproportionately high, an effect that Goldin calls “nonlinear”. In other words, the more hours you work and the higher your income is, then the higher your income will become after time.

What about “linear” pay? This would mean that if you work more, you earn more, and if you work less, you still earn less, but at a rate proportionate to the hours you work. Pharmacy is one example of a profession that utilizes linear pay — and it’s the single high-earning occupation that produces the lowest earnings gap between genders.

Goldin says this is because “pharmacists have become better substitutes for each other with the increased standardization of procedures and drugs,” meaning that “if a pharmacist is assisting a customer and takes a break, another can seamlessly step in.” She therefore accounts for the almost-nonexistent pay gap in the pharmacy industry with technological innovation. And if you’ve ever been to a pharmacy to pick up a prescription, you can picture this, and it makes sense. It’s a simple, impersonal transaction with the customer.

So, do women get less pay for doing the same amount of work as men do? That’s not exactly it. But women do work more unpaid hours than men, which raises several questions.

When a lawyer who’s a mother of two asks for a more flexible schedule and less hours, why?

When a part-time teacher leaves school in the middle of the day to take care of her son, is she still working? Is she perhaps going home to work a second, unpaid job?

Feminists have been talking about unpaid labor for decades.

To this day, domestic and reproductive labor — meaning the work put in to keep up a home and raise a child, which, let’s get this straight, is a shit ton of work — is not considered labor, and housewives or stay-at-home mothers are not considered laborers.

Feminist thinkers such as Wally Seccombe and Angela Davis challenge these ideas, and in their essays explored the nature of housework, which, in their time, was still mostly “women’s work”. The questions they explored are still radical to this day.

To what extent can we “socialize” housework, really?

Can we imagine a world where women are actually paid to cook and clean and care for their own children and husbands — work that does contribute to the economy by providing the workforce with laborers?

Can we imagine a world where, instead of reproductive duties being performed at home so that women are forced to take part-time schedules, these duties become part of the public sphere instead?

Back to the 21st century…

Thankfully, with more women in the workforce, we’re slowly eroding away at the idea that housework is only women’s work, that mothers and wives belong solely in the private/domestic sphere. Yet the fact that this pay gap exists at all, for the reasons laid out above, is proof that some semblance of this idea still endures. For instance, why aren’t men with children, on average, asking for part-time flexible schedules as well?

Some more recent accomplishments, such as mandating paid maternity and paternity leave, give me hope. I strongly believe that some ideological changes still need to be made, that society could also benefit from changing how we look at parenting and housework — what constitutes labor, which member(s) of the household should do it, and now, how it might be contributing to the gender pay gap.

Can housework be socialized? Can companies learn how to pay employees with families?

So, are there solutions to the gender pay gap? Goldin and Davis seem to have two different answers, but their answers are two sides to the same coin, or at least strongly connected to each other. Goldin wants changes to the labor market:

“The gender gap in pay would be considerably reduced and might even vanish if firms did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward individuals who worked long hours and who worked particular hours.”

Davis, coming from a more radical point of view, brings up ideas about “pressing for social services (child care, for example) and job benefits (maternity leaves, etc.) which will allow more women to work outside the home.” This all amounts to what she calls the “industrialization” of housework — moving most of it out of the private sphere.

I think that these are two theoretically viable solutions. However, are they even possible? Setting aside the fact that Davis’s solution is a bit much for American capitalist tastes, think what would happen if, say, education were to restructure their labor force to look the same as a pharmacy. There are just some occupations that do require certain daytime hours and a certain amount of in-office work for the job, industries where personal interaction is so valuable that technological innovation could not simply make up for it.

So yes, being rewarded for the amount of human presence you can provide in the workplace does kind of make sense. Yet, it might still do some good to question the disproportional / “nonlinear” nature of the pay reward given to people who work certain hours.

In any case, these are the questions that we can start thinking about once we get down to what the pay gap really means. While “77 cents” works as an easy-to-remember political slogan, it’s not the whole story, and neither is gender-based workplace discrimination.

The gender bias occurs not within the workplace, but in all of us. It’s all very well if mothers decide to prioritize their children and families over having a higher salary, but it seems to me that men are less willing to make the same sacrifices. These age-old gender roles that we’ve internalized are a huge contributor to the pay gap. Now it’s up to us to decide if this is a solution that we, as a society, want to work towards.