We have fears, all of us. To deny so is to indulge in human hubris, and it's best to acknowledge those fears and know them to avoid that anxiety and survive (or, in an act of dashing pride, face them). I know I fear swimming in open water. A couple of times, when I was very young, I almost drowned in deep water. On a deeper level, I fear losing my friends and losing relationships I put so much of myself of to cultivate.

In a 2015 article in Vox, Emmett Rensin published a first-hand account of how he cultivated a fear of flying and especially flying planes. He opens with an anecdotal lede about a time he flew from Seattle to Los Angeles. It was the worst turbulence he ever felt. There was a power shortage and the plane fell for ten seconds. The lights went out, and Rensin thought he was going to die.

After the experience, Rensin says that "it was still 10 years before I would begin to panic on airplanes...fifteen until...[it] became a kind of long-lede dread, less fear than the gospel of its coming." The worst he feared was takeoff, when he wouldn't be able to watch a movie, write, eat, or drink. Above all, he wasn't able to sleep, "because sleeping means waking just seconds above the ground."

Like we believe in superstition, Rensin made rituals to manage his fears. The first of which was "positive visualizations of landing," telling himself mantras like "planes never crash."

But it wouldn't work. He would be short of breath any time the plane took off. He would always look at the ground and wonder "how so high already?" And then, like most of Rensin's articles, he transitions this fear into something deeper, a larger anecdote of a time he went to the ER for a headache, the reason for which was inconclusive. His symptoms went on, "they did persist, first in the form of a seizure."

He suffered from encephalitis, which his doctors concluded was a result of the result of a staph infection that came from a date who put out a cigarette on his neck. Of course, the doctors didn't know for sure, but this incident 'had briefly compromised my immune system.' From there I had only been lucky."

He took medication. He stopped drinking. He stopped smoking. "I felt, actually, fantastic." And he also confronted his fears of flying and of planes. "The only planes that crash are those with other people in them." Later, determined healthy, he went back to routine life.

And the story reminds Rensin of a friend, someone who had been doing heroin with him in the past and passed out on a radiator, and hours later realized he had burns all over his back. "We avoided him more and more," Rensin wrote. He and his friends promised they'd call the friend on New Year's, but they never did. Two days after New Years, the friend died. The most immediate thought Rensin had was to think of how that could have been him:

"I took heroin, too, but all I ever had to suffer was a long stint in the woods and missing a bit of senior year."

After a while, Rensin was told he no longer had encephalitis, and he felt fine. The scar on his neck began to heal, and he started to drinking and smoking again. But one day on a random October afternoon, he got convinced he was having a heart attack. "I stand...I am dizzy, so I go out on the nearest major street...so that if I collapse, someone will see me. This happens every day for a week." Every day during this period, his heart rate climbs and he becomes short of breath, and he would experience diagnoses of "overwhelming feelings of impending demise." He takes tests, he comes back clear, and he's told that these things just happens.

He goes on Mayo Clinic and looks up hypochondria, which, in his words, is defined as "an illness best self-diagnosed...Is this a joke?"

He was only 24 at the time, and by that time, he was afraid of many, many things: buses, trains, cars, planes, heights, buildings, and ladders. They come once after the other and overwhelm him. He's reminded of a time when he was 21, when he went to see a show on Broadway, and during the first intermission, he heard that Amy Winehouse killed herself. During the second, he learned that his cousin hanged himself, and several days later, he died. It was a couple months later when his date put out the cigarette on his neck - but he lived.

Above all, he feared death, especially in the first 20 years of life. We like to believe that when we're young, we're more adaptable and more accepting of change, and that we're ready to navigate anything. But childhood, according to Rensin is "the belief that history happened to grownups and ended at birth." Adulthood is when we recognize that the world is changing, and changing quickly, but the biggest way the world changes is one day, we're in it. And we notice that eventually we won't be after a while.

Dr. Catherine Belling of New York once called hypochondria "an irrational fear of illness," but that irrational fear was how Rensin survived. "I'm afraid, and I don't want to be," he wrote. He never thought his fear was rational, yet he still had them. He never thought his delusions and fantasies about buses and trains crashing actually had a high chance of coming true.

But even though it was irrational, it was still real. "I am so afraid of dying it follows that I will never really die...We hide small fears inside of big ones."

As much as we think life can change in the blink of a second, the world often doesn't work that way. We don't age immediately, nor does our health worsen immediately. Literary events that have the sky suddenly turning a different color tend to be just that - literary. As much as the years, months, and weeks go by quickly, in the blink of an eye, the truth is that the days go slowly, excruciatingly slow.

Lastly, Rensin transitions into one less stream-of-consciousness thought, about his history with smoking. Whenever he quit, he felt sicker. He felt frail. The soot in his lungs were, to him in some sort of twisted way, a way of protecting him against the world. Although a lot of smokers lie to their doctors, Rensin never did. "I liked when they told me to stop. This was the best part." One doctor, in a moment reminding us that there is humor even in the most mortal of circumstances, told Rensin that "I suppose you know I have to tell you to quit. I am a doctor, after all." But they never told him what to do when he did.

For a decade, quitting smoking was the task at the top of his to-do list, and "procrastinators will [always] recognize the value of a difficult first task." He needed to quit smoking before he quit drinking. He needed to quit smoking before he started eating better or exercising more. In a way, being a smoker freed him of having to move forward, because "so long as I was smoking I had nothing else to do." In fact, he elaborated that smoking was a way of stopping him from reaching the end. Because he was smoking, he had other tasks pending in the distance to accomplish. He had life, and in his words, "I would never reach the point where there would be nothing more to be done."

He compared smoking to his emergency break, "an obvious vice on which to pin every illness, something I could abandon if things ever got too bad and excise any ailment along with it." Quitting smoking was his way of staying "mortal," and I love the word. Perhaps smoking was his way of being immortal, someone among the Gods, and I know it sounds ridiculous but I often feel the same way, because going back to that one vice or the other is a way of not straying into the uncertain chaos that accompanies changing the way you live permanently.

Anti-smoking message boards all over the Internet tell him the same thing: you can't negotiate. There's no "I'll only smoke one cigarette a day." I know this personally growing up among smokers, growing up among a family full of smokers. For me, it's something deeper. I will never smoke a cigarette, because as long as I don't, I am not like them. I am not like everything I didn't like about those people, everything in life I wanted to avoid. But back to the topic: there is no negotiating for addicted smokers. I have seen the smokers I knew and loved give into the peer pressure of one more cigarette with their friends, and relapse into the pack a day they were previously used to. "You smoke or you don't," Rensin writes.

But one time, Rensin did feel like he was bargaining. He looked in the mirror of a friend in Ashland, Kentucky, a month after his last cigarette. For "the first time in a decade, the quit didn't feel like a false start." He told himself in the mirror: "You did it motherfucker. You quit smoking. Now you never have to die."

And what this article shows me, and what I take away from it is that the timing, when he quit, was right. It was natural. I have my idols and my vices, things I worship that make me feel like the life I live will go on forever. I idolize other peoples' opinion of myself. I always need to work and be productive to feel like a useful human being. Take these things away, and then all I have left are people and faith. I'm better at it now, but the timing for completely giving up these "vice[s] on which to pin every illness" is not here, because as long as I have them, my fears will never come true. There's a bottom to the ocean, and I can't drown. I can't lose everything yet.

Recently, that bottom has been slipping. I've been swimming more in deeper waters. I've given myself time to pray and just live vicariously, not as a vessel of God or a puppet, but as someone who can take risks, make mistakes, and trust, trust that God will love him, no matter what. I'm not there yet. I still don't know where I'm going after I die, but one day I might have a manic moment in the middle of the sidewalk, and think to myself: You're free. You did it. Now you never have to die.

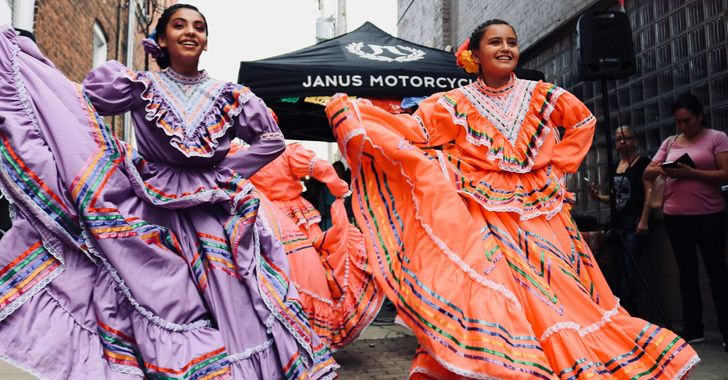

women in street dancing

Photo by

women in street dancing

Photo by  man and woman standing in front of louver door

Photo by

man and woman standing in front of louver door

Photo by  man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by

man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by  red and white coca cola signage

Photo by

red and white coca cola signage

Photo by  man holding luggage photo

Photo by

man holding luggage photo

Photo by  topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by

topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by  trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by

trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by  Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by

Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by  man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by

man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by  difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

Photo by

difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

Photo by  photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by

photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by  closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by

closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by  a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by

a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by  two men

two men  running man on bridge

Photo by

running man on bridge

Photo by  orange white and black bag

Photo by

orange white and black bag

Photo by  girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by

girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by  assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by

assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by  three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

people sitting on chair in front of computer

people sitting on chair in front of computer

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by

two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by  shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by

shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by  happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by

happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by  itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr

itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by

shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by  yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by

yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by  orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by

orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by  5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo

5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by

woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by  a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion