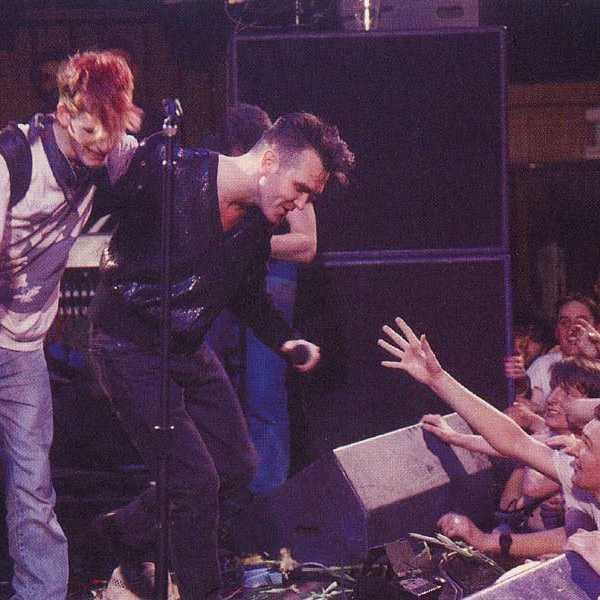

G.G. Allin used to perform on stage filthy, bleeding, and wearing nothing but a jock strap. Throughout his sets, he would frequently pick fights with the audience, all the while proclaiming total anarchy and threatening to kill the president. It’s estimated that none of his shows lasted longer than 20 minutes before being shut down by either the venue owners or the police. He boasted to have been arrested over 50 times and, eventually, he started taking laxatives before a set so that he could throw his own feces at the audience.

For a while, G.G. Allin promised that he would kill himself on stage, and he might have gone through with it had he not been imprisoned for two years, and then died of a heroin overdose on June 23, 1993. A few years later, his tombstone was removed from the Saint Rose Cemetary, because fans of the late rocker made a habit of honoring his memory by decorating his grave with alcohol, urine, and feces.

Believe it or not, there’s something powerfully endearing about G.G.’s music. It’s raw and crass and primal - the shriek of someone completely at peace with his devotion to anarchy and misanthropy. “Bite It, You Scum,” probably his most famous track, is filled with pure rebellious ire; it’s the berserk anthem of someone willing to bask in depravity in the face of authority that countless hardcore acts have spent entire discographies trying to capture.

“F*ck Authority” and “Outskirts Of Life” give the coda of a simple anarchistic creed; one that refuses to place value on anything over than their own happiness. Hell, “Carmalita,” for all its depravity, is a weirdly touching love song; the anthem of someone on the edge of death, looking for someone to spend their final moments with.

G.G. Allin’s songs aren’t poetic, and yet he achieved a certain elegance from just how basic the message is. His music basks in pure existentialism, the belief that the only point in one’s life is to make their mark with as much excitement and gonzo insanity as possible.

The lyrics also constantly embrace the insane paradoxes of this philosophy. One moment he’ll proudly call himself the anti-Christ and make enough insane boasts to put Kanye West to shame, only to then to viciously describe his own death immediately afterwards.

In some ways it’s hard to describe the power of his music without sounding like a complete psychopath, but maybe that’s the point. So much of G.G. Allin’s lasting appeal comes from sheer awe that someone could actually take these kinds of values to their logical conclusion, all the while reveling in his punk-rock hatred of the world, the people around him, and, most of all, himself. This is especially important since these days, people paying more and more lip-service to “telling it how it is,” only to then shriek in repulsion when that puts them in a position of conflict.

We live in an age when billionaire presidential candidates can go on TV and claim that they’ve been persecuted by 'PC Culture,' fully knowing that everyone in the room is going to agree with them. So, in some ways, it’s refreshing to watch old clips of G.G. appearing on "The Jane Whitney Show," standing up in front of a booing middle-aged conservative audience, not only proclaiming “I am the Messiah!” but standing behind the statement so firmly that he'll welcome a fight from anyone who challenges him.

There’s just a tremendous integrity that comes with standing alone in front of a vast opposition and still holding onto every belief that every feature that makes you an individual is inherently good. The power of this image and the themes of his music overwhelm just how repulsive he might have been in person, and sweep the listener up in a momentum that makes them willing to ignore the elements of racism and misogyny that do seep into a lot of his songs, making him a legend in the history of punk.

But embracing this icon comes at a price. Fans love to talk about his crazed onstage antics and his wild claims, yet, they usually shy away from the fact that in 1989 he was charged with rape and assault (while, granted, only convicted of the latter). They love to talk about the pure individualism and anti-authoritarianism that the man embodied, yet try to play down how he frequently toured with The Murder Junkies, who made a habit of incorporating Nazi iconography in their album covers.

A lot of punk forums of Facebook and Reddit have made it their policy to delete any thread or comment that so much as mentions G.G. Allin, and frankly, I don’t blame them. As much as the term “safe space” seems to regularly invoke eye-rolls, it makes sense that online places for people who draw strength and courage from punk rock shouldn’t be littered with the music of an aggressive singer who once created a track called “I Am Going To Rape You.”

When I first discovered G.G.’s music, I’d only been exposed to the side of it that people like to show. I’d heard some quotes, and then I browsed his top tracks on Spotify and was struck by the extreme individualism and existentialism of his songs. It wasn’t until after I’d already created a mental image of the kind of artist he might be, that I then learned about the borderline monster he sometimes was. So the question then remains, is it wrong to hold onto the preconceived ideal I already had?

To someone less familiar with the violent and morbid territories of punk, this might seem cut and dry. But, I’d argue that G.G. Allin isn’t an isolated case. Science fiction lovers still struggle with enjoying the writings of Orson Scott Card while knowing about the man’s unabashed homophobia. R&B music fans are still choosing to enjoy R. Kelly’s music, even though his pedophilia is basically undisputed. Hell, all of America is currently trying to figure out what to make of Bill Cosby’s entire body of work, knowing that one of the most influential comedians of all time was also a serial rapist.

So then where does that leave me, sitting in my room and listening to the beautifully raw anarchistic musings, sung by a human being I should absolutely detest? I know it’s a cop out, but I choose to believe that the art is greater than the man. I think that it is possible to be moved by the artist that I perceive from my selective scan of his work, while willfully choosing not to condone what the other songs and actions might actually entail. At the end of the day, I’m glad that G.G. made the music that he made, and that his mark of raw rebellion on punk history, but I’m also pretty happy that, to this day, people still literally defecate on his grave.