I consider my kindergarten classroom to be the ideal workplace. Each kindergartener had their own “pod” — a designated classroom location containing a small chair and desk that, at any given time, had to house a recreational book.

With this set-up my American school in Hong Kong practiced periods of independent reflection and learning interspersed with group activities. A combination that fostered learning in the extroverts of the class (those who felt energized or stimulated by interaction) as well as their introverted peers (those who were stimulated by solitude and reflection). But above all else, we were praised for our ability to work independently.

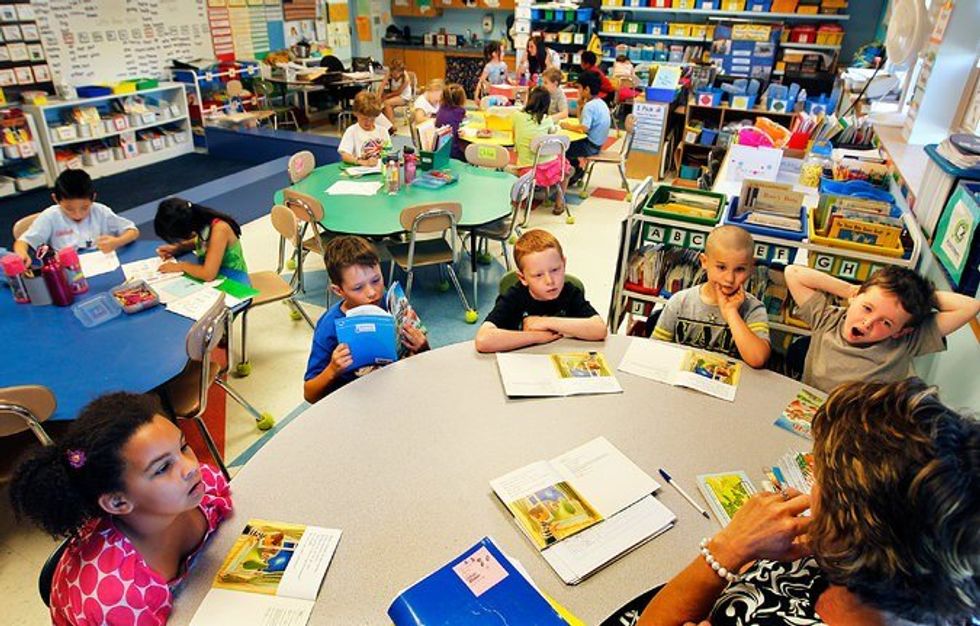

At age 6, I moved to the United States and was thrown into the mania that was the New Jersey public school system. Class was fun but stimulating... perhaps over-stimulating. No sooner would I arrive at school than be met with group activity after group activity and, in later years, discussion after discussion, with team projects and participation marks coalescing into the greater part of our grades.

Instead of pods, we had tables — three or four desks pushed together to form a mass workstation — and failure to collaborate and interact with peers when working elicited strict disciplinary words from the teacher. The table was a formation that followed me throughout high school, a formation that screamed to me this:

Solitude is wrong.

Expressing introverted interests and behaviors now signals a new type of deviance in the classroom. And the U.S. education system’s gradual shift towards an extrovert-centric value system offers solitude a slim chance at revival, though at the cost of student creativity and overall engagement.

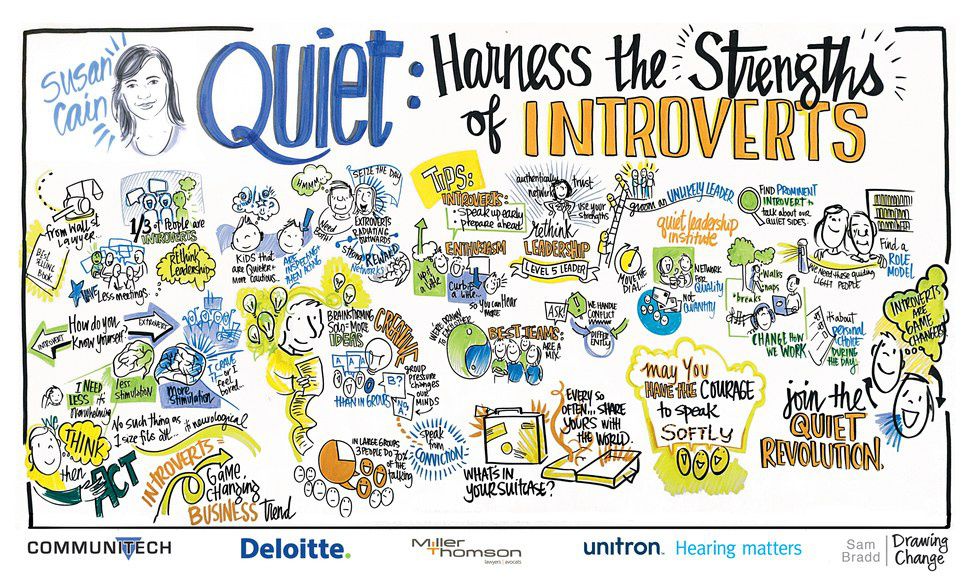

American schools are plagued with what Susan Cain, award-winning author of "Quiet: The Power of Introverts," calls the New Groupthink, which holds that “creativity and achievement come from an oddly garrulous place.” In pre-K to high school, brainstorming and collaborative problem solving are often given priority. Cain writes, “parents and teachers encourage students from the earliest ages to be able to fit in with their peers, socialize, and be able to express themselves and work with the group.”

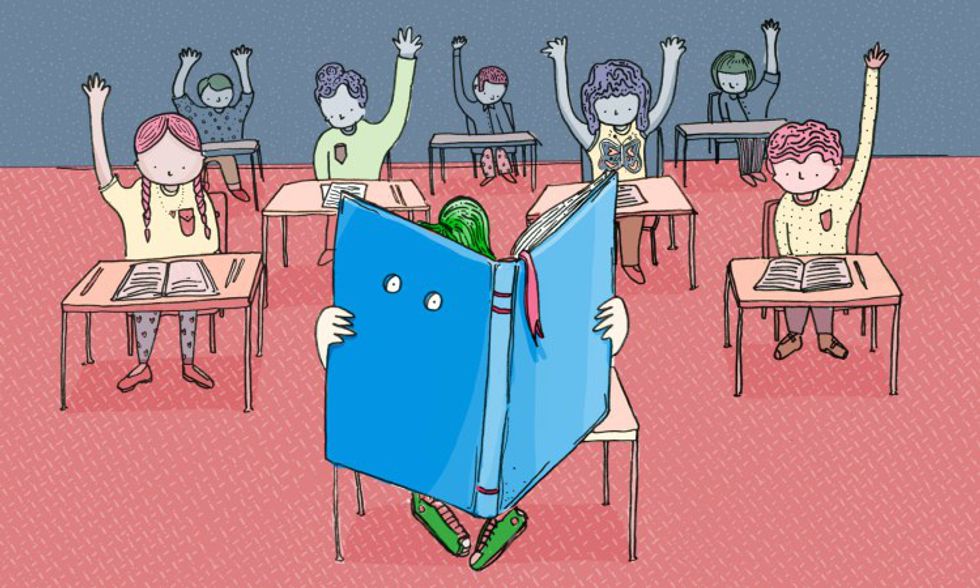

Most tellingly, verbal participation rules as the ultimate test of one’s involvement and comprehension, a fallacy that even infiltrates the college classroom (Most if not all of my class syllabi — Calculus included — list "class participation" as a course grade determinate. And I need not explain how ridiculous it is for the girl on Facebook, Pinterest, and Peach [whatever that is] to be lauded as the exemplification of an engaged student for interjecting random thoughts at equally random points during the lecture for the sake of participation).

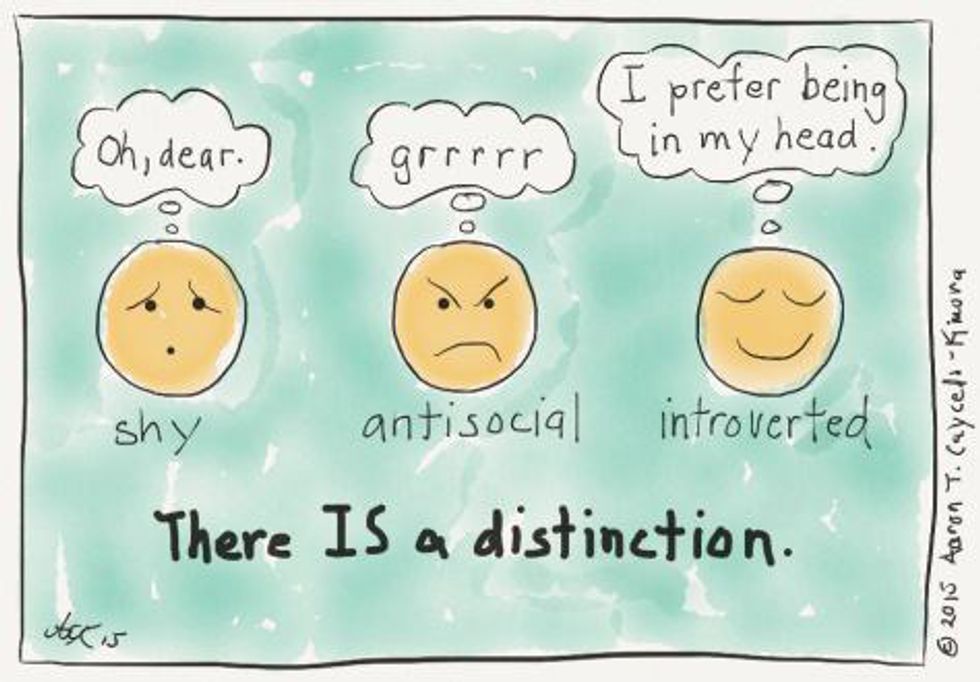

Introverted students who fail to engage enthusiastically in such activities are often criticized by their teachers as seeming unengaged or unprepared. Their reflective natures and often passive learning styles — that include reflection and active listening before vocal participation, not in lieu of it — distance themselves from the loquacious classroom’s meridian of normalcy, as do their tendencies to deviate from the popular belief that to be social is to be happy.

It’s this idea that proves most isolating to introverts, perhaps because American society stresses the importance of relationships in fostering personal growth. An emphasis that is reinforced in the classroom as students are pressured to talk, socialize, and connect tirelessly with peers in order to grow and think critically and creatively. Here, they defy classroom standards.

And yet, the introvert’s preferred method of solitary thinking actually enhances creativity across the introvert-extrovert spectrum, ultimately acting as a catalyst for improvement. Professors Marvin Dunnette, John Campbell, and Kay Jaastad’s 1963 study of brainstorming efficacy concluded that individuals produced more solutions of higher quality when they were allowed to work alone. And, more recently, numerous studies have shown that collective performance plummets as group size increases: Groups of nine generated fewer and poorer ideas than groups of six, and those, in turn, performed worse than groups of four.

Be alone, Dunnette and colleagues appear to advise, for solitude is where healthy ideas are born.

And in their 1998 study of collaborative reasoning, Professors Molly Geil and David Moshman from the University of Nebraska concluded that human rationality may develop via “an ongoing dialectic of individual and collaborative reasoning.” Put simply, solitude and collaboration go hand in hand: Group work nurtures the ideas born from solitude.

The drive to encourage greater learning and creativity through collaboration is admirable, but letting students work independently and in solitude isn’t such a bad thing. And expressing introverted tendencies (like a preference for listening over speaking) should not be seen as an act of deviance. Perhaps it’s time for schools to separate desks once more, to allow each student their own pod to engage with the class in a way that works best for them. Only then can we re-learn that, yes, solitude can be oh-so-sweet.

For more information, please visit http://www.quietrev.com.