It seems like nowadays nobody can walk into a movie theater and not see a movie poster with a 2, 3, or 4 on it.

Make no mistake: today, film sequels are pretty much as inevitable as snow in Alaska. Some might applaud the idea of continuously making sequels to movies they love, while others might bemoan this as a lack of originality and a sign of incoming mediocre cash-grabs.

A quick Google search for the definition of the word “sequel” reads, “A published, broadcast, or recorded work that continues the story or develops the theme of an earlier one.” The word “develops” is one that I’d like to focus on—simply because, to put it bluntly, many film studios that make sequels can’t really grasp what that means. So many sequel films today are either blatantly derivative of their predecessors, overly reliant on new ideas that are superficial or weak, or a step backwards in every way.

So what, then, makes a good sequel?

First, good sequels need to build upon what made the preceding film or films good, exploring extensions of the previous themes and stories. Let’s look at an example.

One of my favorite sequels of all time is "Toy Story 3". The film continues the "Toy Story" series’ ongoing theme of growing up, finally putting the film’s characters face-to-face with the critical issue the series has been building up to: what happens to them when their owner has grown up and is leaving them behind. For those who have seen the previous two films, you might remember some story beats that are in the same boat as the plot of the third film. In the first "Toy Story", Woody fears that Andy is outgrowing him when Buzz Lightyear comes into the picture. Jessie’s backstory in "Toy Story 2"—wherein it is revealed Jessie was abandoned when her owner got old enough—further catapults the "Toy Story" series to the point it reaches in "Toy Story 3". Both of these elements show how far these characters and this franchise have come since the franchise’s inception in 1999.

The second component of a good sequel is the presentation of original, new ideas. This is perhaps the harder of the two to accomplish, but the key here is to make the new ideas meaningful.

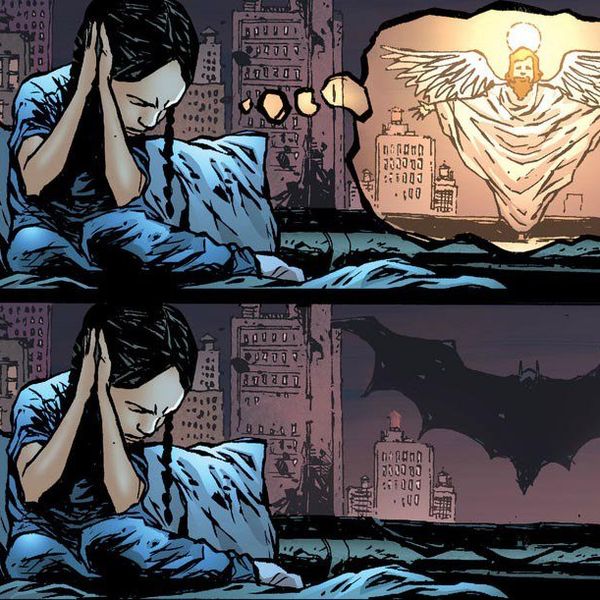

An example of a film that gets this right is 2008's "The Dark Knight", the sequel to 2005’s "Batman Begins". Whereas "Begins", an origin story for Batman, focused on the central theme of overcoming fear and finding resolve in the midst of tragedy, "The Dark Knight" instead chooses to explore the nature of Batman’s crusade. Specifically, it focuses on how his vigilantism teeters along the fine line between good and evil and how far he is willing to go to save lives. It is a logical theme to touch on; in the real world, Batman would most likely be viewed with some apprehension, caution, or suspicion on the grounds that he operates outside the law. This is what makes it a unique, compelling sequel; it provides a complex lens through which the audience can view the character and his world in a new light.

The idea of a sequel isn’t inherently bad. The problem is that the word “sequel” carries with it thoughts of greedy studio executives trying to come up with the most devious plan possible to rake in box office money—a sentiment that is the result of bad or mediocre sequels coming out over and over again with seemingly no end in sight. What studios will hopefully realize is that focusing on the quality of these kinds of films will still in fact yield big profits—the films in my examples sure did, as many other critically acclaimed sequels have. So before anyone out there decides to make "Popular Film 2: The Cash Grab", hopefully they’ll keep in mind this wise parable: if you tell a joke the same way twice or you screw up the punchline, it’s no longer funny.