“I could, and would eat 30 bananas a day.” Such are the words of Jamaican sprinter Yohan Blake in 2013, whose current personal best 100 meter sprint is a staggering 9.69. Blake’s love for bananas isn’t arbitrary: for a top level athlete they are a great choice. They’re portable and tremendously healthy – many studies boast that bananas can lower blood pressure and decrease risk of stroke. I’m confident the third fastest man ever won’t ever have this as a concern – but they are also cheap at the price of 59 cents per pound in my local supermarket, Harris Teeter. So what’s the problem?

In shopping for food, we all consider two factors: price and taste. Were these the only two factors, we’d merely buy foods that were tasty and affordable, or where benefit and cost meet on a graph. Throw nutrition into the mix and suddenly proceedings become a lot more complicated: is organic worth it? What is organic? Is this healthy? Does it have gluten? Such questions can make a ten minute trip to Teeter an hour long slog. The worst however, is yet to come.

Feeding humans puts an immense toll on the planet. To get an idea, look at the way soybean fields cover parts of the Amazon rainforest. So, we should probably look at the environmental impact of our foods as well. It would also be nice to know ‘who’ picked my food from a tree. I also recently stumbled upon Mike Berners-Lee book "How Bad are Bananas? The Carbon Footprint of Everything." The title reminded me: there are two sustainability issues that must be considered. Although invariably linked, carbon footprint is a different issue than environmental and social happenings on the ground.

"How Bad are Bananas?" is all about conceptualizing the carbon output of what we do. Of course, most things we do incur a carbon output cost. The computer screen you’re reading this on does, for example. Berners-Lee’s calculations are not exact, but they are a good marker for how much CO2 is emitted from each item. As it turns out, Berners-Lee loves bananas. They have a footprint of only 240g CO2 per pound, which is nearly fourteen times less than the 3.3kg a pound of out of season strawberries possess. This is because they are shipped by boat, not flown in like strawberries, and require minimal packaging due to their skin.

So bananas are low cost, low carbon, high nutrition. So far, so good. The final hurdle is to check where the bananas came from. My local (Raleigh, North Carolina) Harris Teeter carries one brand, Chiquita, and two types: organic and regular. The organic bananas are grown in Ecuador, the regular ones, Guatemala. The chances of me traveling to South America to find out how bananas were grown were not ever likely given my situation as a broke college student. So, I did the next best thing.

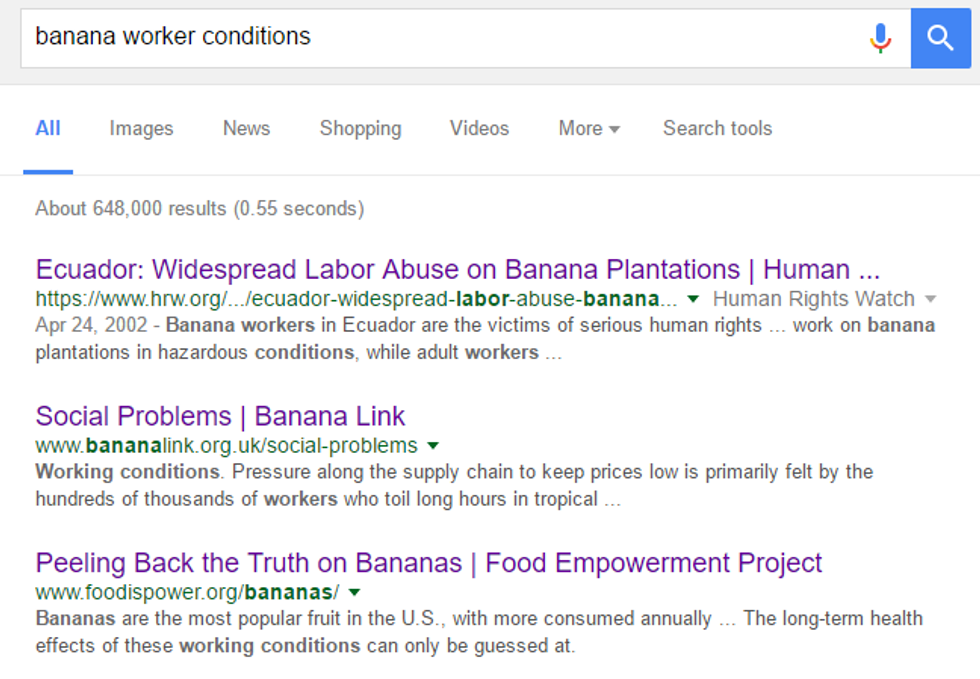

That’s something anyone can do – and read about. As it turns out, the monoculture growing of the Cavendish banana isn’t kind to the environment. It strips the soil of nutrients, and leaves the single strand of banana susceptible to pests. To answer this, banana companies dump copious amounts of pesticides. Bananalink reveals the truth on their environmental problems page, stating, “The health impacts of extensive agrochemical use are numerous, ranging from depression and respiratory problems to cancer, miscarriages and birth defects.” HRW (Human Rights Watch) found other issues in their 2002 visit to Ecuador. Child labor is extremely common, and 90% of the children reported working next to toxic fungicides. Foodispower.org uncovered this video from years ago, which makes a mockery of the working conditions and role of the United States in South American food production. I need not point out the blatant racist and colonialist ideas in the video.

In 1954, the United Fruit Company, the now defunct grandfather company of Chiquita, lobbied the Eisenhower administration to overthrow the Guatemalan government, which the United Fruit Company claimed was leaning towards aligning with the Soviet Bloc. As you may remember from high school U.S history, the coup was successful. CIA trained military opposition ousted the Guatemalan government, and what has come to follow has been a colonial, mercantile relationship between the U.S and Guatemala. The abuse continues today: in 2014 a US court found that Colombian Chiquita farmers could not sue their employer for use of United Self-Defense Forces (AUC) paramilitaries against them, despite Chiquita confessing to hiring such mercenaries. It’s tough to picture Chiquita as the big friendly company when they make friends with a terrorist organization.

Bananas, until now, were a superfood. They are still portable, tasty, climate friendly and healthy. But as far as impacts local communities go there are few histories darker than that of the banana. Their history is so rich – I’ve only started to peel back the skin -- that it can be used as proxy for explaining U.S imperialism in South America over the past couple years. In addition, the oligarchical reign of Chiquita, Dole and Del Monte on the banana industry means the market is essentially blocked for fair trade banana producers looking for opportunities.

Why haven’t we done anything about this?

Overseas unconstitutional negligence by giant U.S corporations isn’t new – but conditions for workers are still harsh and regulation practices are often ignored in fruit producing South American countries. Diffusion of responsibility, a socio-psychological phenomenon is a large part of the issue. The individual assumes they are not responsible because there are so many others partaking; we’re all buying bananas at the expense of workers in South America. It is everybody’s responsibility, and winds up belonging to none. My only hope in writing this is that you’ll consider five things when you shop for food: your regular standards of taste, cost, nutrition, but also climate impact, and environmental effect. Today we just looked at bananas – imagine the histories of all the food which populate grocery stores. As a tip, out of season foods flown in to U.S have a much greater carbon footprint than those grown locally, and Rainforest Alliance certified items are harvested under rigorous environmental, social and economic criteria. As for bananas, I don’t know what to do. For each consumer, the story is different: my Harris Teeter bananas will vary from yours, and Yohan Blake’s. But the first step is to consider that somewhere in the world, someone picked your fruit, and to be aware of their situation. Mindfulness, after all, is the first step towards change.

For Your Convenience:

https://www.hrw.org/news/2002/04/24/ecuador-widespread-labor-abuse-banana-plantations