In recent years I’ve become increasingly aware of a cultural logic surrounding Christianity, namely the belief that there is only one way to do Christian faith, a particularly conservative way, and that one must either accept this way of doing Christianity or reject it in its entirety. For example, you can see this kind of dualism operating in the arguments that typically surround the Bible. With Christians on one side attempting to explain away all of the inconsistencies in the text in order to assert that, yes, the Bible is 100 percent factual, and skeptics on the other side claiming that the entirety of the Christian faith is bunk because those inconsistencies are, in fact, irresolvable. Despite the differences in opinion, both sides have essentially accepted the same terms of debate: that there is only one way to understand the Bible—the conservative, literal reading—and that the Christian faith rests upon whether or not this understanding can be proven to be true.

Growing up, I was presented with many of these kinds of either/or frameworks: only through being a Christian could you be a moral person. Only through being a Christian could you be saved, the Bible can only be trusted if it’s inerrant, you’re only pleasing to God if you’re straight, you aren’t a true Christian unless you believe in traditional gender roles, Christians must reject evolution and so on. Though not often explicitly stated, these were the underlying assumptions of many of the authors I read, the mentors I listened to, and the teachers who instructed me in the various faith environments I participated in. Over time, the continual reinforcement of a single way of viewing the faith created a deeply subconscious feeling that the conservative evangelical way of understanding Christianity was the only possible one—you either agreed or were wrong. And thus anything that threatened to deconstruct that worldview was viewed as dangerous, inimical to faith, and ultimately worthy of rejection and disproof.

The difficulty, of course, arose when I found myself in an environment where I had to critically examine my worldview from perspectives that didn’t already presume the correctness of what I thought. Throughout the beginning of college I increasingly found myself in a position where what I was learning resonated with me on a deep intellectual, emotional, and moral level, but conflicted with the values of my faith. Because of the dualism I had been raised with, there were no apparent ways out of this conflict- I either had to convince myself that, actually, what I was learning was wrong, or reject my faith and move on in spite of the personal cost. What would I sacrifice, that which was opening me to new ways of understanding and loving others, or my faith?

From what I’ve gathered in my interactions during the past few years, listening to the stories of both people my age and generations that have come before me, my experience is not that unique. Countless numbers of people involved in faith communities have faced this exact conflict and have struggled to reconcile the disparate and intransigent forces pulling on them. However, what I have noticed in my conversations with non-Christians is that many likewise believe that the conservative version of faith is the only possible way of understanding Christianity. They have bought into the logic of the either/or simply because this is the only version of faith they’ve ever been exposed to.

Yet as I’ve continued my education, I’ve discovered that—despite the amount of times I had been told otherwise—there is indeed another way. In fact, there are many other ways, many other understandings of faith that have the potential to break up the constellations of conservatism and open the self and the world to a more compassionate mode of being.

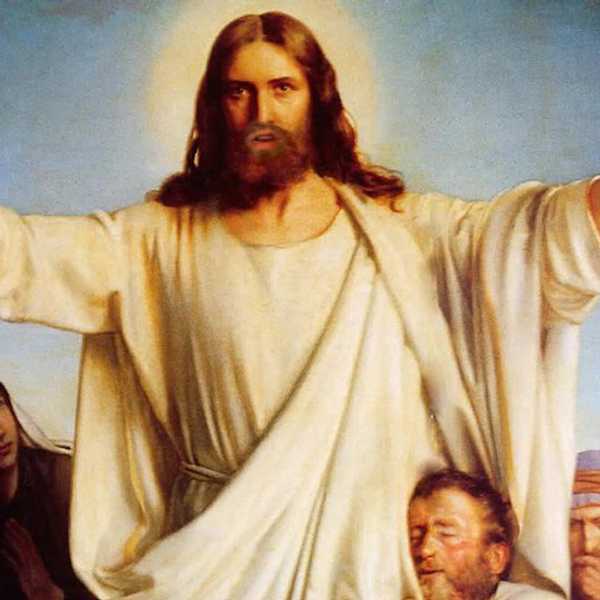

My hope in writing for Odyssey is to share what I’ve learned in the past few years with the aim of carving the way for a more progressive Christianity, one that does not suffer from a black-and-white world of forced choices but transcends the limited options afforded by the most visible forms of American Christianity today. A Christianity that might actually be a force for good in the world, one that is in the business of shaking up our privilege and presumptions and setting fire to whatever it is that holds us back, personally and societally. A Christianity that truly encourages us all to be well, regardless of our sexuality, our gender, our race or our religion.

Although my hope is that my articles can provide guidance for the many who have found themselves conflicted and dissatisfied with the forms of faith they have been raised with, I am not primarily writing for that audience.

Rather, I am writing for those who have been deeply hurt by Christianity, the church, and individual Christians, and have ultimately been cast aside. I think of friends who have been kicked out of congregations because of their sexuality, or who have left the church after being subjected to constant sexism. And I think of my lovely friends, deeply thoughtful people, who’ve vowed to never even come close to Christianity because of the destructiveness, anti-intellectualism and conceit of Christian people that they’ve had the misfortune to witness.

I am writing to let you know that there are people who are listening and value who you are and what you have to say, not out of some perverse desire to trick you back into the church, but because we genuinely care about your well-being. There are those of us in the church who hold you dear and are working to make sure that the pain that you bear will never have to be borne by anyone again. So please, help us to make this a world that is safe for you by continuing to share your stories and experiences, knowing that we will do our best to listen and act in your interest.

Grace and peace to all.