@Berlin Graffiti is like nothing you've ever seen. It's been called a graffitti mecca. Its straight-up world-renown tourist bait, in every place from the train stations to the Berliner Mauer itself. Now don't get me wrong. Philadelphia is not graffiti-shy. It boasts its dubbed title "City of Murals" for its pioneer government-funded arts program. But more on that later. What surprises me here in Berlin is all the tagging. Tagging is signature graffiti, or putting your street name on public or private property without permission. Society often immediately and solely dubs taggers as vandals. We see it in movies where 'hooligans' or 'hoodlums' use it for revenge. Where 'thugs' hang out every night in graffiti plastered alleyways. Where the 'at-risk' youth stir up trouble. These stereotypes may have their founding in druggies, gangs, and small-timers, but at the end of the day its a negative or falsely interpreted picture of life by the media. Murals and street art, however, are often more accepted. What's the difference? Graffiti is communication between different graffiti artists, a way of bragging for individuals as they build up their own Rep, or for gangs marking territory. As an outsider, I enjoy the color and life but can sometimes hardly read the letters. And rightly so, because its not for me, but rather street art and murals are the messages for everyone. They're glimpses into the circles passerbys aren't permitted to enter, revealing narratives of injustice, fighting against ignorance, and being sarcastic or satirical throughout. Whatever content, the latter is a crack into the cave, as it were, made for the passerby by the initiate.

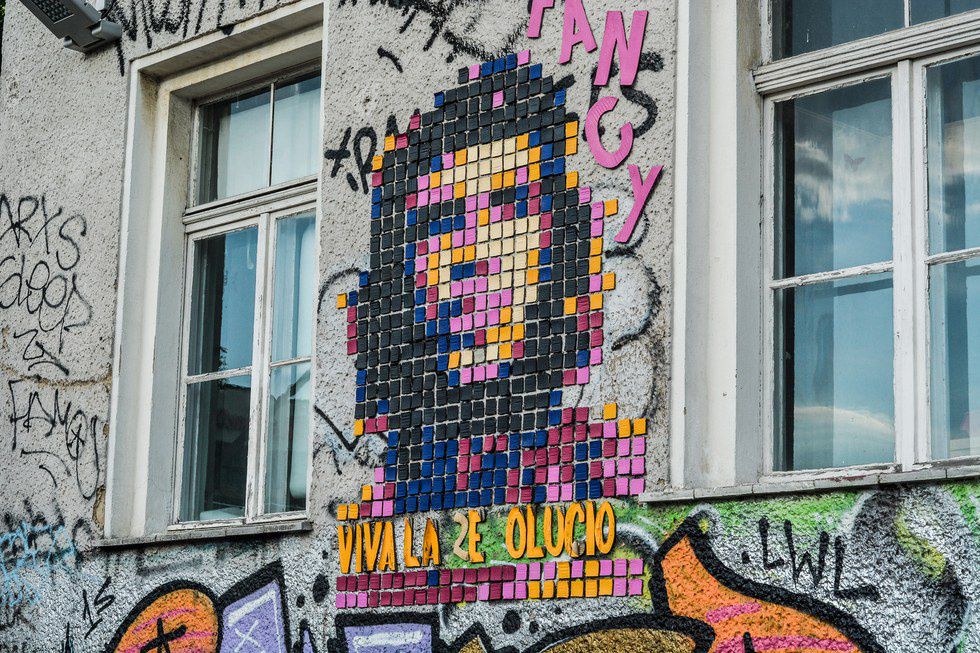

(East Berlin; Alley near Warschauer Park; Aaron Henry Photography)

But both communication and message in Berlin aren't just 'how it is'. This pair has been around since cave drawings and all throughout architectural history. In Berlin specifically its been very functional. In West Berlin (held by allies, from the Russians) during the 1960s different marginalized and silenced voices began to use the paint to speak. With the wall up around East Berlin, the DDR was deciding to fence in its artists, attempting to de-politicize their film, writing, and of course visual media. However West Berlin turkish immigrants, anarchist far-wingers, and draft-resisters still had freedom on their side. When the wall came down in 1989, the east was open pastures to both east- and west-Berlin artists.

Thus graffiti is flow in the city. It especially has been life-blood to todays residential, business, and tourist city, a system to transport energy and ideas boldly to everyone, whether as a dare or a caution between fellow-taggers or a fourth wall break to reveal the hard truth of politics and society. One such example is Tower. One began to see the name pop up on posters, bumper stickers, or small signatures. Later they began to also reach walls, stairwells, shipping crates, and trains & stations. Soon after people understood. His work harkened to guard towers, skyscrapers for workers controlling but not owning the city, the Fernsehturm (TV tower) itself, originally built 1965-69 by East German architects to air their state-sanctioned shows.Tower was bringing attention to how towers controlled lives.

Surprisingly, it's all forbidden and illegal by law, yet tourism it procures is a hard deal to wave off. Chief Detective Marko Morvitz said in an article that he is against the crews not mainly for the act of making art or because they do it on private property, but because in his view it contributes to gang culture and that even presently some gangs carry arms while tagging. But what do I notice as Im merging more into European culture? With my eyes screwed on like Gordon Parks' or Baldwin's

Tagging or creating on someone's private property is hardly ever gucci, but on discarded crates, buildings, and cement stairways is clever. Two, p

rettier tags, no matter their content, are far more preferable. Bubble letters, with contrasts and different color shades usually take less heat. I asked multiple people and they agreed, even I did myself. One feels like art, the other feels tacky.Three,

they aren't afraid to let the people play their drums. They took ours away in North America and left us with dust-stomping and hand-clapping, absolutely and rightly afraid that our unity by speak ing in back and fourth and by standing in the ancestors who come before us through dance, song, and beat would make us stronger. They took away our drums and still do. In America we allow FaceBook but criminalize graffiti and tagging. Of course Europe is no political or social utopia, I write that especially as a blind-spotted US citizen. But when society affirms something like graffiti because its creates such expressional freedom, I know that Berlin's government dares to be openly challenged more than my own.

(More from Warachauer str. Aaron Henry Photography)

I was gonna close writing here, reflecting more on drums, on young artists, on Tower, and on the importance of travel, till I heard about Philando Castille and Alton Sterling, then later entered to a building yesterday right near the TV tower, Tourist town. It's a tall building of 14 stories but after communism and before the west, many people flooded East Berlin for cheap or free housing. Formerly government owned and used to house workers, it was now empty, so young artists, drug users, gangs, and small-timers made home. Going down hallways my guide explained that graffiti had been on every wall. People would use their blood from needles to tag the stairwell walls and would drop the heated spoons they used for heroin, leaving hundreds of tiny dark scars on the flooring. This was not easy to see. This had been life for some people, I realized, hard, dirty, tough to take in just like the 'bad graffiti'. With no camera, I took no pictures. (Taking pictures of non-aesthetics is often hard enough emotionally. ) However, it was beautiful to see the work of an artist whom our guide, the building manager, had commissioned for the stairway. These experiences reminded me of a quote from the comments section of one article I had read it: "most graffiti is raw and unpleasant like the truth you don't want hear."

As more poor artists will continue to use their money for paint, pick a concrete canvas and speak, its our challenge as viewers to know our history and to affirm both scrawny graffiti which feels uncomfortable but is often some symbolic form of reality, not with pity but earnest respect. We must also understand more appealing work. Its done with more money, took more time, probably done by a commission. Imagining the stories behind the art in Berlin and Philly (stay tuned for part two) that are less often told puts us in a ready position to receive them.