On Friday, November 13, I had the pleasure of listening to the Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk tell a story. He told a personal story about how he managed to turn his 2008 bestseller, "The Museum of Innocence," into a museum, tucked away in the streets of Istanbul. The museum cost him $1.5 million -- the entirety of his Nobel prize winnings -- plus the amount of time it takes him to write half a novel. It opened in 2012, four years after the novel's publication, and yet, Pamuk insists, "It’s not that I wrote a novel that turned out to be successful and then I thought of a museum. No, I conceived the novel and the museum together.”

Pamuk began collecting items for his imaginary museum years ago. He would wander the mysterious shops and colorful bazaars of Istanbul, on the hunt for unusual objects to add to his growing collection. He explained in an interview once: "The humble flea-markets in the streets of Çukurcuma, shops selling bric-a-brac from old tables to ashtrays, from cutlery to the locally made toys of my childhood and places selling old magazines, books, maps and photographs all stoked up a desire in me to somehow put what I saw in a frame and preserve these things forever." In 1999, Pamuk purchased a small 19th-century building in the Cukurcuma district, with the intent of one day converting it into a museum to house his collection of curious objects. He says once he bought the house, he knew he couldn't just establish a museum; he planned to write a novel using the objects he had collected over the years. Pamuk continued to purchase a random assemblage of items -- from antique salt-shakers to cigarette holders to old taximeters and cologne bottles -- and then wove them into the storyline of his book. Just as a mystery writer uses clues to create his plot, Pamuk employed his compilation of objects to develop his plot. He spoke about his process of writing and how he intertwined the newly purchased building, his many objects and a storyline: "If this house was going to be a museum, then the imaginary people who lived in it should use the objects that were now piling up in my office. So I began to imagine a story that fit in with the street the house was on, with the neighborhood itself, and with the objects I had collected. Over the course of eight years, this story evolved into a novel, rewritten over and over again as I found new things to display in the museum, until it was finally published."

And so, "The Museum of Innocence" is written around Pamuk's unique assortment of over 1,000 items which include earrings, a tricycle, ceramic dogs, lottery tickets, and more. The novel tells the tale of 30-year-old Kemal, an upper-class man in Istanbul who is engaged to be married. Yet one day, he stumbles upon a beautiful shop girl, Füsun, and immediately falls in love with her. The story details the lifelong obsession Kemal has for Füsun, as he collects various mementos that remind him of her and the affair they shared. Each of the 83 chapters in the book is centered on at least one memento which Kemal has obtained. By the end of the novel, the accumulation of Kemal's keepsakes cause him to build a museum to honor his beloved Füsun. As The New York Times' J. Michael Kennedy eloquently put it: "For a time Mr. Pamuk became Kemal, looking for pieces that reflected each chapter as he wrote it, searching the junk shops of Istanbul and other parts of the world. The collection he assembled reflected not only the plot of “The Museum of Innocence,” but also Istanbul during Turkey’s halting movement into the modern era."

Shortly after the publication of "The Museum of Innocence," Pamuk began what he refers to as a "Disneyland kind of project," which was the creation of his own Museum of Innocence. Pamuk has been intrigued by the concept of the "small museum" for a long time and believes small museums are much more personal than state-run museums. He has mentioned in the past: "When we visit larger, grander museums, it is always with a commentary, a historical explanation running in the backs of our minds. But small private museums are more open to individual stories." Whenever Pamuk travels, he always hits the smaller museums first to "experience the private world and the vision of a passionate individual." On Friday, he explained that during his childhood in Istanbul, there were very few museums and that museums are like novels, in that they have the ability to speak for individuals. He discussed that he is against large museums like the Louvre being the blueprint for future museums because they do not represent an innocent perspective; they are sponsored by the state and thus are representative of the state not the individual. He connected this thought with the Turkey of the 1970s (when the novel takes place), describing the state's strength of power and how the culture was very narrow-minded at the time, with state-sponsored TV channels. He explained that it felt like there was just one culture and how he believes that without small museums, a similar homogenous culture can arise. Inspired by small museums such as the RenaissanceBagatti Valsecchi Museum in Milan and the Frederic Marés Museum in Barcelona, he attempted to evoke a similar individualistic vibe in his Museum of Innocence.

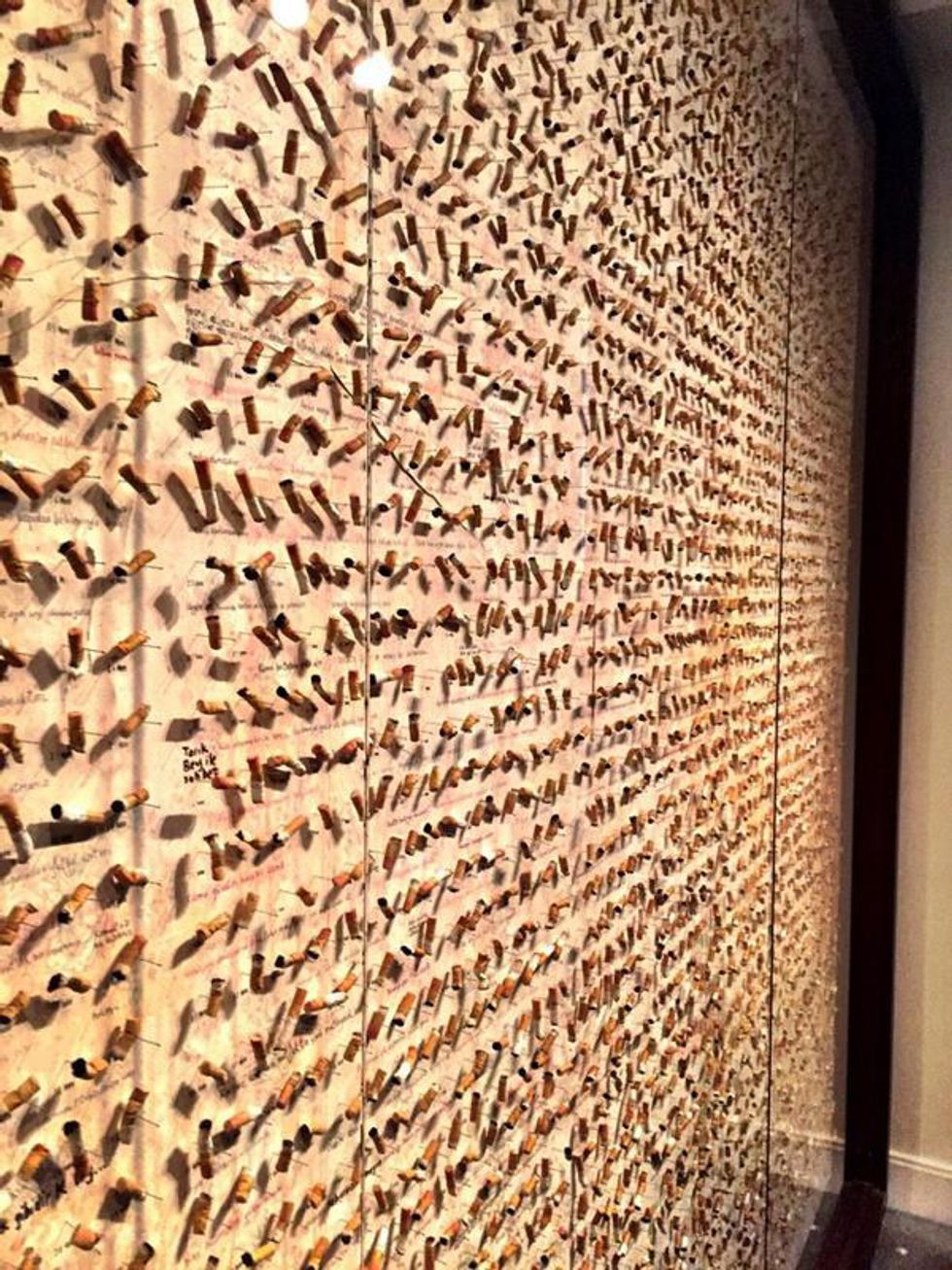

Pamuk explained that if you visit his museum, you will not find much of himself within the walls. After all, the museum is based upon a fictional story. He said in an interview: "Very little of me is here, and if it is, it’s hidden. It’s like fiction." He has noted that both the novel and museum invoke sadness and the sorrow of Turkey in the 1970s. The four stories of the 19th-century household 83 cabinets -- one for each chapter in the book. The relics represent Füsun, this fictional character. Visitors are swept into her world: a make-believe tale that they temporarily believe is true when surrounded by her "past belongings." People wander through these displays, which are arranged in the chronology of the novel, beginning with a cabinet housing Füsun's earring, which falls off when Kemal bites her ear in the first chapter. By the end of the museum, visitors realize that they are amidst a work of art, convincing them that this fake character really did exist. One of the most convincing exhibits is the wall of Füsun's 4,213 used cigarettes which are crumpled and lipstick stained. Pamuk admitted on Friday that they are, in fact, fake cigarettes and were smoked by a vacuum cleaner. He also mentioned that each cigarette's shape was carefully considered so that it was molded according to Füsun's mood.

The best part of the museum for author Orhan Pamuk? He loves to watch the exhibits trick visitors, making them forget that the person whose objects they are observing is, in fact, fictional. Additionally, he has said: "I’m always glad to see visitors discovering firsthand that what is being displayed in this museum is not simply the plot of a novel, but a particular mood, an atmosphere created by objects." Pamuk said himself on Friday that objects by themselves are innocent, and so, by arranging all of his collectibles together, he has created a unique aura. And as character Kemal says in the novel: "Museums are the repositories of those things from which Western civilization derives its wealth of knowledge, allowing it to rule the world, and likewise when the true collector, on whose efforts these museums depend, gathers together his first objects, he almost never asks himself what will be the ultimate fate of his hoard.”