Politicians often talk about “investing in their communities” by implementing government programs looking to “bring jobs back to X” and “invest in Y’s future.” Indeed, a central tenant of Keynesianism, one of the most popular economic schools of thought, is that government spending is needed when citizens’ consumption and the market’s private investment isn’t enough to grow the economy. This increased spending provides jobs, enhances infrastructure, and spurs on consumer spending and investment, which then increases aggregate demand, which helps the economy grow. This seems to be an accepted fact to many politicians. However, does it describe the reality?

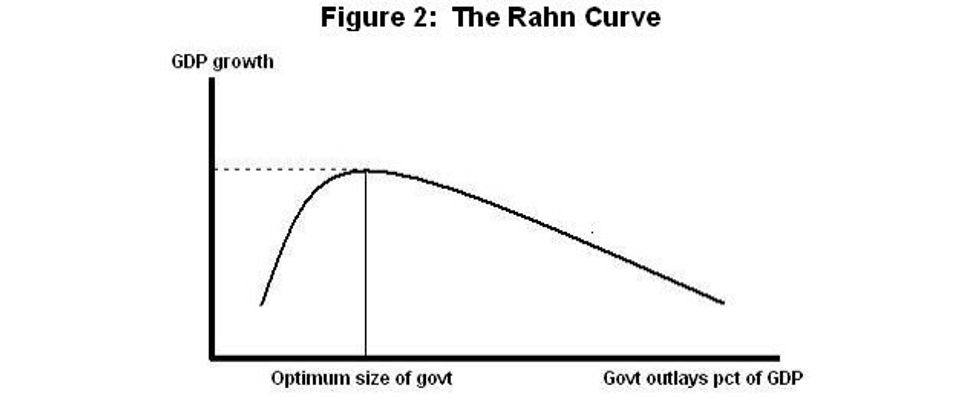

The Rahn Curve

In 1996, economist Richard Rahn developed a comprehensive study of what government spending as a percentage of GDP maximizes economic growth. He concluded that too little government spending prevents the government from carrying out essential duties such as enforcing contracts, establishing the rule of law, and protecting the individual. These services create an environment conducive to the establishment of a market economy. However, too much government spending in the economy increases market misallocation, burdens businesses with regulations, decreases competition, and reduces economic growth as a result. Rahn concludes that a range between 15 percent and 25 percent of GDP is ideal for maximizing economic growth. This allows the government to create a safe environment for a market economy while allowing it to essentially run on its own from there on. To give an idea of where the United States lies, the United States government spending is around 34 percent of GDP.

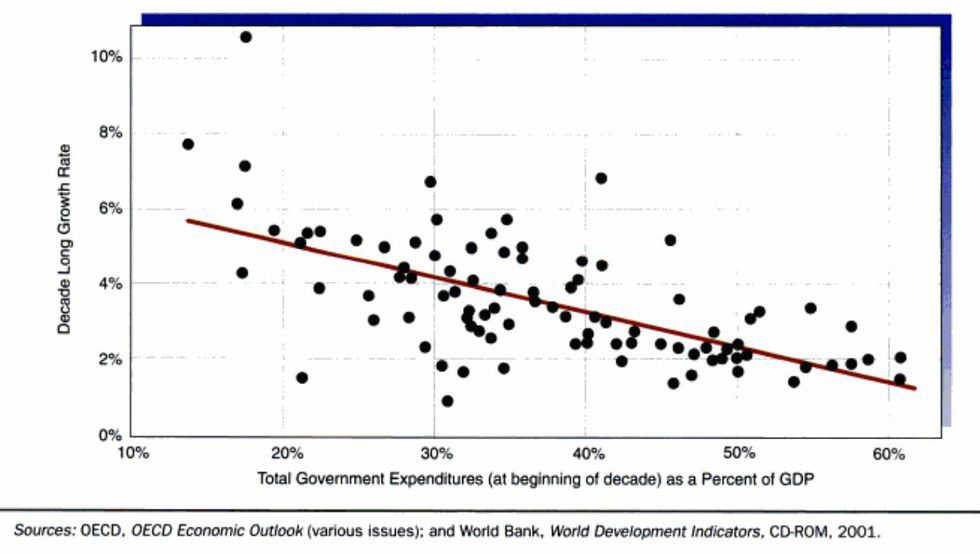

Government Spending vs. Economic Growth

Does government spending correlate with economic growth? Some evidence suggests that there is actually a negative correlation. A 1999 NBER paper “Fiscal Policy, Profits, and Investment” concluded that reductions in government spending and wages lead to a reduction in business profits and an increase in investment, which increased economic growth. A reduction by one percentage point in the ratio of primary spending to GDP in the sample OECD countries leads to an immediate increase in the investment/GDP ratio by 0.16 percentage points. It leads to a cumulative increase by 0.5 percentage points after two years and by 0.8 percentage points after five years. This effect is particularly pronounced when the spending cut is achieved through lower government wages. A cut in the public wage bill of 1 percent of GDP leads to an immediate increase in the investment/GDP ratio by 0.51 percentage points, by 1.83 percentage points after two years, and by 2.77 percentage points after five years. The opposite is true of increases in government spending, as investment and profits decrease, which dampens economic growth. Data from the World Bank illustrates a negative correlation between increased levels of government spending and economic growth, seen in the picture above. The correlation may be partly due to different countries being in different stages of economic growth (more developed countries have less economic growth than developing countries on the rise, as they don’t have as much room to grow). However, there is certainly significant evidence that government spending does, indeed, lead to less economic growth due to its effects on private investment and profits. The data certainly calls the widely accepted notion that increased government spending leads to economic growth into question.

Why?

Increases in government spending might reduce investment and thus economic growth because government spending “crowds out” private investment and puts wage pressure on businesses, which reduces profits. The only way that the government can perform any action is to first take funds away from the private sector. So, while the increased government spending provides some services that may provide benefits (but most likely not an extensive amount), it also adds new bureaucracies, reduces efficiency in different markets, wastes money that could’ve been used to bring better goods and services to the economy, and burdens people with taxes. Although it’s easy to look at what is immediately seen with government spending, Austrian School economist Henry Hazlitt argues that the “unseen” or less readily known consequences are severe. What’s unseen is the loss of more efficient, more productive, and less burdensome private investment. The money taken away from the private sector could’ve been used to innovate and increase production in the marketplace.