My parents never told me I had to be anyone, but they showed me that I could become anyone - by saturating me in creativity.

Years and years ago, a racing track was established on the outskirts of my hometown for BMX championships. My brother wanted to race. It was financially unfeasible by any traditional means, with wilted purse strings to show for it.

“Broke and that’s that” has never been the end zone with my family. My dad spent three months walking through our neighborhood on garbage night, going through people’s curbside junk piles for bike parts. Sometimes he would drive into other neighborhoods and towns on the way back from work to look. When he struck lucky on a functional frame, he’d get his hands on spray paint, and make the bike he built look brand-spanking new. My father found safety helmets and pads at a Salvation Army and one bike became two – a red and purple, my brother’s and mine.

On nice afternoons when the track closed for the day, we’d hike up and we’d ride for hours. My parents would pretend we were motocross stars, sometimes inventing grand prizes (usually $1 ice cream cones – the rare treat of an oasis to sweaty kids with sore muscles). They talked about their day, picnicking on a blanket with my then-infant brother, and stopped to cheer whenever we shouted, “Hey! Watch me do THIS!” before taking off down a steep ramp.

We didn’t need trophies or teams. The reward was getting away with being up there, living in our daydreams.

We were privileged enough to have a vehicle most years, albeit junkers, though my dad usually had it at work with him during the day. When we’d go to see summertime fireworks, we’d park a street over from the crowded viewing fields and sit in the back of my dad’s half-jalopy truck, wrapped in blankets.

In a region where it seemed impossible not to run into someone that someone had a history with, my parents kept to themselves often. The rides we chose at carnivals were often about which had no lines to wait in, and bustling festivals were never quite as fun as the quests we could invent while climbing a mountain, or biking at a dam walkway, or discovering an empty lake to spend the day at. Our adventures were our own, where there was nothing and no one to limit them

This is what happens when your parents are young and poor: you can’t go to any of the places the kids at school brag about, or even half the places in town, so you discover all the nook-and-cranny places you CAN go without a dollar in your pocket, and you make it the most exciting thing in the world. You carve out a space for you and yours, then cherish it.

On lazy afternoons, we’d drive to all the playgrounds in our neighborhood, trying to stay one park ahead of the crowds and leaving once they arrived. Other days, we walked downtown, or attended free lunch days for low-income kids at the town park, sharing the three paper bags among the five of us. Playground structures were pirate ships on the high seas. If my younger brother wasn’t chasing after me over chain bridges or across monkey bars, one of my parents was. When we discovered a frog in the river behind our home, we would build it a tiny house out of twigs and leaves before naming it and speculating on the details of its illustrious, crime-filled, mobster-family-drama amphibian life.

On paydays, we could afford to drive two hours to the nearest airport and watch planes take off from behind tall fences. My parents would bring reusable bottles full of instant powder juice, and set each of us up with a dollar-menu McDonald sandwich. We picnicked on the grass by the side of the adjacent road, and closed our eyes. My mom would tell us to imagine we were on the plane, to picture a “magnificent trip”, and then asked us to go around in a circle, describing where we were flying to, like relatives at a thanksgiving dinner counting blessings before the prayer.

She often asked us to just imagine.

To her, she was regifting Wayne’s World. To us, she put us on the cusp of flying away from all the hurt and heartbreak always ricocheting off our fragile glass walls, ready for Neverland. Who cares if we're in foreclosure and apartment costs are higher than the mortgage payment, higher than our means even on overtime weeks, right? Right? Who cares if dad works so much if he reads when gets home at night, right? Right?

Once upon a time, I was a poor kid in an under-resourced school who wanted to go to college. In my hometown, any activities you wanted to do you had to pay through the nose for. I wasn’t the kind with the resources to do organized sports or lessons, though my parents tried. Every once in a while they skipped paying an important bill so I could take a three-session dance class with some barely-qualified 20-something instructor.

We were broke, always. It was all we knew. It never occurred to me that the lack of access to events, lessons, or activities might ever be a terminal barrier to doing the things I wanted to do when I was older. We could event tense races out of a space, or think ourselves to departing planes.

Most often, my parents invented creative enrichment on their own. It didn’t have to be a monolith institution, or a grand gesture. If it wasn’t the entire family dancing in the kitchen, then it my mom confidently asking waitresses for extra pens so we could all draw on restaurant place mats back during our traditional-if-infrequent Friendly’s $3 to $5 breakfast. If it wasn’t my dad building birdhouses out of wood scraps, or hovering over an annual $3 seed garden that fed us through hard seasons and filled freezers better than it should, then he was constructing a handmade play-scape out of wood and bolts leftover from an odd job that had paid him to haul them away from a neighbor’s yard.

My mom was once high-school thespian and aspiring dramatist. My dad dreamed of being an artist from a young age. College degrees weren't possible to them as young people. They stumbled onto their interests awkwardly, with novelty and without apprenticeship. Whatever they taught themselves, they passed on. They were brave, they were inventive, and they were kind. Or at least, they were masterful at making sure that's what my brother and I saw and emulated. It was enough.

Books were everything, as exciting as the Disney movies we played over and over, relentlessly (and Mr. Rogers, Bob Ross, Supernatural, and Smallville marathons in the expected odd-motley). I grew up with my dad reading JRR Tolkien or CS Lewis or Madeline L’Engle or Laura Ingles Wilder to us before bed, sometimes after roasting marsh-mellows in an old woodstove and camping in homemade living room tents, or making castle forts with the couch cushions.

They treated holidays like full theatrical productions. They decorated every corner of our home, made whatever decorations they couldn’t find for pennies, and turned designing the tree into an all-day event. They threw themed parties of music and snacks and movie “screenings” just for my brothers and I, and created elaborate traditions that bridged on performance surrounding Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, the Tooth Fairy, religious figures and angels, ghosts, and the invisible elves that create mischief or watched for goodness.

Our world was a lot of both goodness and mischief. My dad would stop by the side of the road to fix a broken-down car without hesitation, or immediately went through a drive-through for a bag of cheeseburgers when he passed homeless sign-holders – even if paying for it came from the quarters he’d use to pay for lunch at work. My mom, pretty and sweet, could smile her way out of anything – even exploring private property when wandering off trails as we hiked, or wandering into rooms or spaces that sparked curiosity despite implying ‘keep-out’.

I don’t know if it’s because we were broke, or because my parents had moved away from most of their naturally disconnected extended families, but they doted on us. They listened to our stories and delighted in simple things. At least for the first decade of my life, it almost seemed like they never lost the novelty of having brought tiny humans into the world, building the family they both longed for as children but never had in their respective homes. They read to us, played with us, and gave us a taste of bravery and a dream about having or becoming more.

The most important thing they ever gave me was a compassion for other people’s needs, and a complete disregard for judgment. When we danced, or sang, or used fake accents, it never mattered who was around. It mattered that we were enjoying ourselves. No expedition deserved to be boring because of trivial social norms.

As one can imagine, as a kid, I was a shameless firecracker, sweet as honey but nothing short of a tornado. Not messy or unkind, but loud, expressive, dramatic, and musical in the way that insecure people – adults or kids or whatever – just wanted to stomp on or snuff out. Teachers hated fidgeting and banter, no matter how flawless your grades. Once past the age where anything unique was “cool”, kids never accepted the social deviancy of creativity and boldness. I dressed up in my mother’s hand-me-downs to go to school, in a boa and leather boots in third grade or full sequined prom gowns in forth or old Halloween costumes in fifth. I was growing so fast and my mother’s closet was more affordable than constant shopping – and "owning it" involved me begging my mother to paint my face with cheap K-Mart eyeliner, marking my temples with hearts and leopard print and stars to make the school day my own expedition.

Some fit more poorly than others, some were more extreme than others. It didn’t matter. Teachers and peers took issue with everything. I’d read books well past my grade level, but be punished for using different voices for different characters when asked to read out loud. Disciplinary hearings were called because I “never read normally” (always too fast or too theatrical), or because I’d draw on the backs of handouts while waiting for everyone else to finish what took me just a minute or two.

I was accused of plagiarism, or copying down memorized limericks because what I handed in was always “too imaginative” or “too articulate” for my cohort. At one point I had to march around a school that had never heard of air conditioning in pre-summer heat, reading what I’d written to every other teacher until one could pinpoint where I’d allegedly “stolen it from”. I didn’t, so we didn’t get anywhere. The teacher’s paranoia grew and harsh accusations got crueler until an overheard phone rant confessed it: “Where does a kid get a mind like that?”

Surprisingly, my two brothers and I ended up in polarized situations. The one just a year younger than me – I’ll call him J here – experienced the same dislike of classroom structure. Despite his legalistic obsession with rules, best behavior, and informing the teacher of peers’ “crimes” – his inability to hold still for hours at a time got him held back a grade level, even as endeared teachers proclaimed him an easily lovable favorite.

Meanwhile, I kept testing so far ahead that administrators frequently petitioned to have me skip grades. Teachers withheld me because they believed I was socially inept. (Apparently it never occurred to them that selective quietness is something that happens when you’re told every five minutes to “stop talking in class” and “stop distracting the others while they work”. Their demands often backfired --- only shouted in the first place because I was always fast-finished and told to wait in agonizing boredom for everyone else to finish while prohibited to work ahead.)

Eventually, my brother J became his younger peer’s funny, example-setting, upstanding-citizen ringleader.

Meanwhile, I ended up staying home every few years, claiming “homeschooling” while I self-unschooled, only to return the following year and easily test past the cognitive skills from the year I’d missed, skipping my own way without the luxury of saving time.

My littlest brother, “R”, is nearly a decade younger than I. Following in his elder siblings’ footsteps, he was moved to an on-scholarship private school, where he plays with animals, uses computers and games in structured but self-paced classrooms, and has the emotional support needed for a gifted child with disabilities.

Though as his older siblings we weren’t so lucky, we did do fantastically in high school and even better in college.

I’ve attend a prestigious institution on a full-expenses-covered scholarship from outside organizations, study stage acting and directing, have a radio show, paint, play guitar, write, make films, and find my way into novelty experiences and hobbies on the whims of curiosity. J’s following the dream of being a cop, something he’s been chasing passionately practically since he left the womb, and is masterful in a program that emphasizes role-play simulations as on-the-job-experience, only benefited by his improv-acting group bonding classes. He sends me out-of-this-world creative Snapchats every day, and whenever we speak, he’s either handling a brutal job with charismatic humor or in his car, on the road, racing off to climb mountains and towers and adventuring into cities we never knew as children.

We both lead by example to our youngest brother: play is a choice you make every day, adventure is a lifestyle, and being unique is the greatest thing in the world. Schools aren’t designed to see that. It’s your life, brother – now tell me a story. I love that silly voice you used when you told me about your day. What book are you reading? See any good movies lately? Tell me everything that happened.

My great grandmother used to see us once a year, when we’d save up to pay for gas just to get to Vermont and she’d cover lodging for New Year’s week. There was no TV up north unless it was the ball dropping on New Years, or Days of Our Lives – but we got free access to any of the toys our many many many cousins and second-cousins, who also visited but we rarely ever saw or even met, left behind on their visits. My grandmother kept only the best and weirdest, dolls and things, or toys people would give her. She was a true matriarch, the family woman of the neighborhood.

Our family felt massive, endless and as far reaching as the many corners of the earth back then. We had unknown relatives that seemed mysterious and exciting, especially as we were ignorant to the tragedies and cruelties of absent fathers or shattered relations that caused the immense estrangements. The little trailer-convert home might as well have been a palace on all that land, full of steep and sprawling curvatures, rich and thick with tall green grass.

We sled down roller-coaster hills, climb trees that stretched above the rooftops, and roam through the guest rooms filled with whatever our many cousins left behind as we all cycled in and out. We’d think about what belonged to who and try to piece together personalities of these other kids we were related to based on found objects.

As we roamed the yard, we’d pretend to be explorers. On the rare time we got up there in the summer, we would graze the blackberry bushes and look for deer, or pretend we’d find lost Alaskan sled dogs, or a skeleton buried in the leaves, to solve a mystery or a murder. Cool rocks became magic stones. All the birds could talk and had messages meant for you from faraway places.

While not particularly exotic, our favorite left-behind toy was a nameless, hand-me-down doll. My brother’s attachment to it lead my grandmother to send it home with us, and from then on the game Mommy, Daddy, Kid was invented. In our Connecticut barely 1/8th of an acre backyard, my brother and I would take his doll and go on an imagined trip, with the path delineated with something as simple as walking around growing flowers (always weeds, but petal pretty nonetheless). With “Kid” being the doll, fondly named Baby, we commenced on a routine we repeated relentlessly. It always started on the almost-tree house play-scape my father built, particularly as filled with thin pear tree branches that grew through each space in the wood panels, sticking in and out. That was the mall, or a diner, or a police station, or a store, and so forth.

Eventually we got a plastic playhouse when the neighbors moved away and left it behind. It became a bug-filled paradise for us, a pastel pink and blue eyesore that delighted us more than anything.

Whenever we’d stop for snacks, we’d run into the house (and deal with the laborious efforts of getting mud off our bare feet, with not tracking mud and pool water being our my mother’s one “serious” rule aside from kindness to one another) and visit what we called her restaurant, “Bonnie’s Good Food”.

Signs were made and destroyed with spills or crumbs, faithfully. I was a ‘mommy’, so we used my mother’s first name at her shop, much to our awkward giggles. She’d deliberately cut our sandwiches fancier. She turned food into weird, playful art, long before the days of web tutorials or Pinterest, before any other moms did it – and said, “Bon appetit”. We always thought she was making a ‘Bonnie’ pun and the impression of cleverness stuck. We thought she was a genius. Everything she said was always new and brilliant, and she would happily take credit for movie quotes or clichés, even as she laughed at our wonder, in the dark to her plagiarism. Innovation itself, quick wits and new discoveries, were a constant joy - the kind that never seemed to lose their novelty.

Our imaginations were wild and endless, and they delighted us. So many parents were stiff and formal, limiting their children and compulsively intervening on our games, terrified of our apparent madness, no matter how harmless. Their children always seemed soft-spoken, unsure, and terrified to make a sound --- or, alternatively, cruel tyrants quick to spawn multi-room disasters, breaking whatever they touched. We went through dozens of friends, and so few stuck around, or could keep up. My parents were too young for the thirty-something parents to find company of similar minds, and we exhausted other kids with our lack of convention and endless energy.

The days were long and sunny. It was just my brother and I, and later on, our “real baby” --- my kid brother Robert --- and sometimes one of the 30 foster kids we had in our house over the few years before adolescence. We didn’t understand what moved us, only that we were always moved by something. The catalyst for happiness was always a small light inside out own hands. If you have a flashlight, you stick it in your mouth and make your cheeks glow. If you have a marker, you draw a cartoon, or trace the veins in your wrists. If all we had was slippery socks, we’d run in tiny circles together, over and over, until we collapsed from dizziness or slide across the floor – we shouted “Scooby Dooby Doo! Scooby Dooby Doo!” until our words slurred, believing it made us run faster.

The games were based on finding exceptions to the limits – something I’ve internalized forever: If all you have is a neighborhood kid come over to visit, you take him around your house and come up with ridiculous things along your tour. Point to an overhead light and call it the old baron’s chandelier. Point to the fridge and say that’s where you keep monster’s eyeballs in jars. Point to a storage compartment in the ceiling and call it The Grudge Hole, find the hidden rooms in the attic walls and talk about the cave men that live there. Talk about your mother’s vases – they’re full of snakes that come out when you play your recorder. Even a clogged drain is a claim that Cousin It visited and used your shower. Closets are gateways to Narnia, the holes the dog dug were used up portals to wonderland. The bathtub is full of rubber ducks and water boats made for pools, and it opens up a tiny world’s oceans when full, where you play Marco Polo by yourself or be an explorer or turn into a giant sea monster, or fifty foot tall mermaid. Basements are filled with ghosts, attics are filled with elves, and even the angel that watched over us was always hiding around the corner.

We created entire towns and characters in our subpar sliver of heaven in a town that was somehow both small and industrialized, filled with old lots and the waste from long-dead factories, urbanized with sprawl and decay and urban plight in an always-one-person-removed-from-someone-you-know population.

We had our slurry little accents and words that meant something different from the common use. Our yard seemed like the greenest, wildest, prettiest place in the world – it had mini fruit trees and grape vines and rhubarb and dogs and a cheap K-mart pool that was held together by duct-tape and the knowledge that if we collapsed it we’d never have another, and it was all enough.

It was free. We loved each other. We fought over who was to blame for accidents and injuries, but never shot each other down. Everything was a good idea. Everything was exciting. Everything was fun – and when it was too dark to be outside, only then were we allowed to give our imaginations to the TV.

In the evenings, we were obsessed Supernatural – for the games we invented about it more than anything else. It was something we watched through the hands over our faces, peaking through spaced and trembling fingers with squee and a fluttering heart, hitting each other with pillows and diving off the coffee table into a sea of blankets during commercials from the euphoria and thrill. (It was our American equivalent of Doctor Who: we stayed up late to watch it from where we hid behind the couch.)

We’d pretend to hunt monsters and go to bed with flashlights, scaring each other as we explored the basement or the attack until we slept over in each other’s rooms, dragging one mattress from across the house to the other’s bedroom floor. We’d make forts strung with lights and filled with every stuffed animal soft enough to sleep on – anything with no scratchy neck bows or sharp buttons or hard noses. We’d pretend hurricanes or tornados or bears were outside, and hide in a chorus of midnight laughter that rang above my father’s demented, resounding snoring.

It was wonderful. We were limitless.

Tragedies came and rolled – a foreclosure threat, or a stack of late notices. Not being able to continue going to a class because of money, and never seeing new friends again. Failing epically, falling into fast-casted injuries, or being humiliated by a particularly shaming adult who couldn’t handle a disrupted day with children playing peekaboo in the racks of clearance clothing. My parents weren’t ridiculous – we often played the quiet game in stores, or ate before leaving the house so we’d sleep in the back of the cart on a pillow of a winter coat’s downy padding – but bad-humor and a dislike of play is everywhere.

As long as we were clean, never wasteful, and respectful of other people’s spaces, nothing else mattered.

“You’re bigger than this town… ‘Keep your feet on the ground and your eyes on the stars.’” It’s the oldest story in the book – and it became our mantra. They called me Princess, they called my brother “Ninja” – full on nicknames. My littlest brother weirdly was “The Snack Fairy” and “Ginger Boy”, but that’s another story. Those titles became the heart of every story, and how we talked about ourselves.

Those years of our lives, we could do anything, be anything. My parents never cared what we chose to be, with two conditions: “as long as you choose something [and work towards it]” (my father) and “as long as it is good for you and your body and you are happy” (my mom). Limits were something that came from the outside, beyond our nobly defended castle walls. They refused to be our first bullies, always citing instead, “Life is hard enough.”

While my mom trailed behind me, watching but never constricting, I ran along the streets of the distant, weirdly silent, seemingly always windy downtown. We all had trademarked Big Brown Eyes, but mine were more than that: they were awestruck, clever, observant.

One of my earliest memories of my hometown, forever on a dream-hazy repeat like a familiar record, is the far gaze up, up, up at the glowing marquees and neon signs. When we walked under the town’s world-renown conservatory and the well-known theatre, I was dreaming about a world so close but entirely inaccessible.

These were completely out of place institutions, situated in restaurants geared towards tourists. They weren’t affordable, or even accessible, to most people that lived there. I wanted them all the same.

Pleading to my folks, who were always guilty for all that they couldn’t give no matter how amazing they were, couldn’t change our financial situation. They made it clear that I could do anything if I just made it to college – their one dream for us, though they tried to never push it – but in the meantime, the stage was an adventure I had to make myself.

Fast-forward to their never-ending think-tank, when my parents would lay awake and believe me to be asleep in the next room, just talking. Talking about how they hoped they were doing okay as parents, what they wanted for the future, who they thought we kids might be someday. Some nights were problem-solving. I wanted to perform – so my dad decided hit the road.

Specifically, he went Dumpster Diving, which is not as what sounds like and involves no actual dumpsters. It’s what they call the combination of thrift-shop-hopping, stopping by secondhand department stores, and driving by the side of the road to look at things people put out in hope someone will pick it up so it won’t go to waste.

Eventually he found a karaoke machine. I’d sing into it, drag friends into joining me when they would, and make mediocre webcam videos on the world’s oldest computer – a Goodwill find. All you need is a little tower and a monitor that won’t electrocute you, no internet necessary, plus a $3 used webcam the size of an orange to sit on your old school Windows monitor, a come-with-the-programming Media player to playback, and a writing program to write stories, of which I wrote thousands of pages.

I didn’t have the computer until I was 12, but from the time I was an infant, they filmed me on an old 90’s camcorder. Learning to crawl, to walk, to dance, to flirt, whatever. Later it was just singing and dancing, or wrestling my brother, or recitals of talent shows. (There’s dozens of these videotapes left, although the bulk was destroyed in an accident involving a combination of melted pop-sickles on the tape cabinet leaking through the cracks, and a fatal orange soda spill that finished them off.)

In any case, it wasn’t how they recorded – but what they recorded.

My mother was the kind of woman who never threw away anything that gave her an idea. People always brought her clothes, because she was beloved by anyone who met her and her socially-pleasant flair for the theatrically dramatic, just like our money problems, were never secret. She was friends with anyone, and they brought her tributes and gifts like wise men meeting baby Jesus, or suitors courting a princess. Acquaintances and friends would bring her bags and bags of thrift store donations. She’d keep and clean and hang all of it, never being afraid to give something away when someone was in need. With hand-me-down ottomans from her sister and found mirrors, it became a personal dressing room

Pulling from her makeshift costume shop, I’d dress up in wild outfits, sequined coats or leopard scarves or black sweeping wool coats or faux furs. She loved anything that looked like Halloween costumes.

She’d turn on an old stereo and pull out old exercise equipment that was either on extreme clearance at Wal-Mart, like a clear-out markdown mini-trampoline, or a treadmill my dad found. She’d exercise while I’d go through all her clothes, improving shows and reciting tales of quests or epic loves in rhymes that I discovered only as I spoke. She called these pop-up performances “fashion shows”, crying out for poses and encores.

It all took place in an amazing walk-in closet that my dad hand-built, self-taught handyman he was, out of storage space in the attic. He used the same skillset to excruciatingly build elaborate dollhouses, to hand paint the miniature Wal-Mart guitar I’d received for Christmas. He’d make holiday themed canvases, or draw portraits of my brothers and I, and design his own tattoos. He built half of a work truck from wood and two hands, relying on it for years until it was run into the ground and falling apart like a ramshackle jalopy that never should have seen the road in the first place.

My mother painted our faces, made our family costumes, and invented extremely visual recipes (all while teaching us that taste is all that matters in the end anyway). My father built my brother a wooden race car bed, full of rocket-shaped drawers. Together, they covered our childhood bedrooms in murals of trees, aliens, birds, and planets in space.

They made everything, and anything. Only my dad’s sour face and typical inner-old-man grumpiness ever got in the way of full commitment, and even then, he’d find a way to have fun watching us do whatever embarrassing thing terrified his own self-consciousness. He fondly called us “artists” and treated us like we could become anything. My mom told us we were better than the morose, grumpy climate of our admittedly restrictive New England town. We believed them.

They never told us we had to be anything in particular. They never pushed us towards interests or activities we didn't love ourselves, but instead shared their passions and helped us find our own. Every day was an adventure, a stage play, a wonderful dream. We were allowed to fall, and to fail, and to make mistakes -- and "normalcy" didn't matter so much (so one can understand how I became a gisher).

Yes, I am often accused of looking back on the hard times of childhood with rose colored glasses – the kind that cloud fights, disasters, tragedies, illness, mental health breaks, hair-tearing stress, high tension, chronic insecurity, bullying, and the worry for what comes next. In the mess of all of this though, there was also the beginning of a lifetime; of learning to love the uncertainty; of getting good at the week-to-week hustle; of thinking outside the box at every rock in the road. Muscles of grit and resilience were built alongside dreams, one brick at a time.

In this space, a few quiet, amazing seeds were planted, while others, long-ago-sewn by my parents, came into bloom.

First, you learn teamwork before you know what you’re even doing. You’re collaborating with people all the time to make the most of your opportunities, to help them make the most of their opportunities, to make sure everyone is having a good time: even if the goal is to have the best and most interesting day ever. We set out to do that every day. Caring for the people around you, being invested in them, being interested in them? That gets you far.

Wanting the extraordinary, wanting goodness, wanting an experience, looking after each other, being excited about literally any and everything you can get access to: that does something for your storytelling I can only begin to articulate here.

Even more importantly, being willing to make sacrifices or to work around lack of resources because that is your existence: you’re living like an artist. You’re also inclined to maximize your opportunities naturally, for the pleasure of it, and never miss a shot. You’re in the right headspace to get somewhere. You’re naturally resilient, and happy inside that fight, and understand a wellbeing beyond materialism or easiness. You live for the ultimate joy each day. You never settle for tedium within even the most mundane tasks.

They taught us respect for others, compassion, and bonding beyond what many know in a lifetime. They taught us storytelling. They taught us bravery, and adventure.

Did they make mistakes? Of course they did.

Was every moment of every day happy and blissful? Of course not.

Did life get harder as we got older? Of course. Of course. But they taught us to find silver linings, to dream, and to opt for self-awareness instead of self-consciousness, and only worry about judgments from others as respect for the people around you necessitates. They gave me everything I needed to love and be loved, to make art, to live with the audacity to chase happiness, and to know that life can be good even when it will often be unhappy. I grew up with resilience and grit through hardships, eternal links to my siblings that no one will ever understand, a heart full of joy, and eyes for the big picture instead of sweating the small stuff.

Our parents are only human, limited to what they know, and inevitably going to mess you up somehow.

As I get older and I enter the life-building era of one’s 20s, I look back not at the failures they were terrified of (despite the inevitability), but at the abundance of gifts that a life people who are money-focused would think of as “less-than” or “sub-par”.

Success – in one form or another – was never a huge leap. Rags to riches, on paper, is a vast journey. However, when you’ve had enough of going without, you learn a few things. First, having lemons to make lemonade is a privilege. It’s the abundance of having all that you need - even if it's tough to work with.

Second, finding beauty in pain, or making banquets out of table scraps, is only as hard as your perspective.

Third, doing well under pressure, pulling it together in a pinch, and making something out of nothing are a matter of your resourcefulness, not your resources.

It was real life. We had fears and bruises and epic humiliation and self-inflicted wounds. It was not a dream world; it was our world in which we infused dreams.

Art, storytelling, and happiness – in one form or another – was an inevitability.

In a world where every weakness was an asset, and every obstacle an adventure, the ending belongs to you. My parent’s philosophy is simple: you don’t need money to live, but your kinds need your time. Time is what you put all together: story after story, one adventure after another. Eventually you become someone, who loves someone, who raised someone. Eventually you've lived a life.

All you needed was time – and in the end, it’s all you’ll want more of.

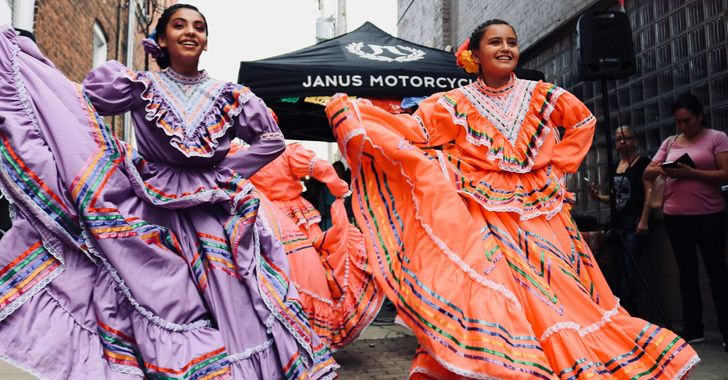

women in street dancing

Photo by

women in street dancing

Photo by  man and woman standing in front of louver door

Photo by

man and woman standing in front of louver door

Photo by  man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by

man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by  red and white coca cola signage

Photo by

red and white coca cola signage

Photo by  man holding luggage photo

Photo by

man holding luggage photo

Photo by  topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by

topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by  trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by

trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by  Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by

Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by  man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by

man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by  difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

Photo by

difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

Photo by  photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by

photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by  closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by

closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by  a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by

a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by  two men

two men  running man on bridge

Photo by

running man on bridge

Photo by  orange white and black bag

Photo by

orange white and black bag

Photo by  girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by

girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by  assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by

assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by  three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

people sitting on chair in front of computer

people sitting on chair in front of computer

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by

two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by  shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by

shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by  happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by

happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by  itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr

itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by

shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by  yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by

yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by  orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by

orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by  5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo

5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by

woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by  a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion