If I had to pick which one of us would end up killing an innocent person, I guess I’m not really surprised it was Ryan. Ryan, the “almost-always-king-of-the-hill,” the airsoft arms dealer, the dirt path daredevil. Every neighborhood has a Ryan: that kid who’s outside all hours of the day, with a card clicking along the spokes of his spinning bike tires, and scabs on his knees that look so much like asphalt you aren’t sure which broke…the skin or the pavement. In Ryan’s case, it was both. And a broken clavicle, and cheekbone, and windshield.

I got the call while I sat in the “office” on my lunch break during my shift at the farm, Kel’s stupid little selfie filling up my screen, buzzing, buzzing. I answered it in the oblivious and positive (no, not neutral, not ever neutral) way that people just have to before they receive such bad news.

“He what?” I asked. I remember staring out the window at the stallion in the bullpen across the way. The owners don’t have any bulls, but they call it that anyway, as if verbal traditions are as heavy as the pen itself. The stud kicked the post, pent up.

“He-he was drinking this morning…and-and he, uh, he hit this lady…” she trailed off, crying into my ear in a way that made me see her lips pursing into a bow, chin scrunching into something like cellulose. I’ve known Kel since preschool, and let me tell you something about Kel: she was the girl who sat at the arts and crafts station, gluing feathers down to paper until her joy reminded her of home, and it made her cry. And cry.

“Okay,” I stayed calm, “Where is he now?”

She paused on the line, said, “He’s at the courthouse. They’re just holding him until he can go to trial.”

As I stared at the horse, pacing around in the mud, whipping its tail at flies, I thought of Ryan, plastered to the cell bars, fluorescent lights casting black stripes on his face, arguing his constitutional rights. I thought of him actually knowing them, and of the guilt finally sinking in on his flushed face as he falls back against the concrete, sliding to the floor, and how he comes to the conclusion he is exactly where he should be, given the circumstances.

“Okay,” I said, “I have to finish work, and then I’ll head over.”

Somewhere past the stallion, over the hill, the river, and the sprawl of houses on the other side, I could almost see Kel sitting on the floor of her bedroom, peering out the window at both Ryan and my houses across the street. She probably had binoculars, was probably trying to see if she could catch Ryan’s mom crying. Or maybe my mom would open the side door of the house and walk through the grass to the neighboring front door. Maybe she’d bring cookies she baked, or a box of tissues. Kel probably wouldn’t be able to make it out, but she would speculate.

She was the one who called the cops for me the first time they came to check on my family. If she hadn’t been peering in my window, I wouldn’t be sitting where I was, sick at the idea I was glad it wasn’t me who was dead.

“That’s all you’re going to say?” She huffed, “God, you’re an asshole.” Three beeps, and she was gone. Kel used to tell me I didn’t love my mommy because I didn’t cry when I was away from her. If I had known the word for it, I would have told her I had priorities. Instead, I tried to cry, too. It never worked.

Before I even put the phone back in the drawer, it lit up with notifications, vibrating against the wood where I couldn’t see it, like a cat stuck in a box it ventured into and discovered it could not escape. All my friends spread the news to each other, crying how could he, and what got him to this point?

What did get him to this point? After all, that’s a valid question. I walked outside and kicked my boots against the stone wall to my left, then walked through the grass to the garage. You have to kick this door at the bottom to get it to open, but I have it down to one continuous motion. Inside, it was damp and cool. I grabbed the weed-whacker hiding in the corner and dragged it outside.

I looked down at the tool in its entirety. At the gas tank, two-toned, shock orange on top, plastic white and nearly transparent below, like the underbelly of a toad or a dragon. I analyzed the cap, which coughs out sweet gasoline fumes when you twist it off, the vapors swimming around in the summer air. How did Ryan come unscrewed?

I looked at the rest: a ripcord (which is a term often reserved for parachutes, but that’s what I’m calling it) a black handle with multiple switches, the same orange as the tank, then the rest of the machine, its long neck like a sword someone stabbed into the ground, shiny metal near the hilt, down to where green wraps all around it after years of cutting grass.

And this is where we get to the important part: the whacker itself, a thick black disk with a safety guard like the guard on that sword I mentioned.

I walked down the gravel driveway, kicking rocks as I went, until I arrived at the fence line. Goggles on, I yanked the cord and the weed-whacker roared to life, purring in my hands. I lowered it to the grass in between the wood posts, and had at it.

Grass vanished. So quickly, everything cut down. The head spun faster than I could track, its two orange wires blurring into one as they leveled the earth.

It was a carousel, the playground kind without the horses or carriages, one two kids escaped to on a summer night, the beer laughs of parents fizzing on the surface of the sunset. Fireworks cracked into nothing in the sky, a brief and brilliant explosion, so bright and beautiful. Then, only smoke.

It was a carousel, one that spun slowly, with glossy gridiron that warmed the skin even after the sun said goodbye. These two kids - these two kids you can only look back on as characters and not the people you used to be - they ran in circles, hands on the bars, pushing as hard as they could. Never fast enough, so when the going got tough, they jumped right on, holding their sparklers out to the darkness, flames flitting out to the grass, just singeing the ends of the blades.

But I squeezed the trigger harder than I should, and the weed-whacker spun faster than any carousel could. Besides, one kid’s dad came searching for him, yanking his stubby arm as he stumbled back to the party. The grass vanished.

It was the carousel, rattling as the two teenagers dropped a car engine on its platform. “Never fast enough” wasn’t enough.

It was the carousel, Ryan on its back like he owned it, his hair cut short, a cigarette dangling from his mouth, gas can dangling from his hand. Spin, spin, and spit the gasoline away into the grass, lighting it from the end, one orange stream of fire blurring into one circle, the ground charred black, seed never growing back.

And he wanted that grass gone, more than anything else. He wanted to spin his vision out of existence to escape the town we grew up in, his daddy wouldn’t come searching for him if he could just go fast enough, the grass wouldn’t tangle around his legs and hold him down.

The whacker kept spinning, I squeezed its trigger even harder in the tall grass, because it didn’t want to get stuck either. Sometimes it wasn’t fast enough, and its entanglement was simply a consequence of where I chose to put it.

Is it possible to feel empathy for a machine? Getting stuck, you work and think, “This poor bastard. I learned not to make that mistake years ago.” Ryan and I knew. If you were in the garage carving a bayonet out of willow branches when the door opened and either dad’s car pulled in, that was a whip on the ass with the same branch. Or the neck. Or face. We always raced each other wherever we went, but somehow we never were fast enough to avoid our dads.

But Ryan did go fast enough this time, at least fast enough to kill someone. Fast enough to land himself in a room with security, where no one could reach him from the other side, not even his parents. Maybe it’s not a question of how he killed someone, we all know he drank until he couldn’t see the road, and smashed into a mother of six, showing her daughter how riding a bike goes. No, maybe it was why. Why the fuck did you kill someone, Ryan?

With that question on my mind, work became a blur, and everywhere I looked was a memory.

The only time we ever sat still on the carousel, Ryan sat on the side where I couldn’t see his bruises. He had a military school uniform folded in his lap. He stared off across the yards and the road, to his opened garage, his dad’s car hiding in the dark, waiting for him.

“I wonder when I have kids, if it will be their fault, or if it will still be mine.”

“What?”

“Is it me, or kids like me?”

“Dude, I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“You know…that kid in the neighborhood. The kid that gets sent to military school. That parents don’t let their kids play with. Where do they come from?”

“They come from their dad’s penis.”

He looked at me, but he didn’t laugh. I went quiet.

“They come from their dads,” he repeated back to me.

“I’m that kid, too, you know,” I said. “We’re those kids together. Twins.”

“Then why am I going and you’re not?”

And I found myself asking that question until I found myself at once in front of him, his familiar face on the other side of the glass. And then I asked where he had gone. I sat down and grabbed the phone. He grabbed the other. He was in orange.

Twins. Same shit dad, same neighborhood, same model house, same scars on our knees, same spin record on the carousel. But he was on that side of the glass, and I was on the other.

Why him and not me?

And I wanted to look at him as clearly as I could, but the glass was smudged and dirty. He tried to say he was sorry, but all I could see was the orange of his shirt, and sparklers. A kid with long hair and a tentative smile, no idea what he would get himself into. I saw each year that led to this on the glass in front of him, and I saw his scalped hair, charred and black. I saw the past and gasoline. But mostly, as I tried to look right through to him, I only saw my reflection, and that of everyone I grew up with, all my friends, coming in behind me. And for the second time today, I found myself sick at how glad I felt it wasn’t me.

My head kept spinning, and everything hit me in a way I didn’t let it before.

I opened my mouth and started to say something, but so did he, and the voices crashed against each other on the line.

Someone said, “I’m so sorry,” but I could not possibly tell who.

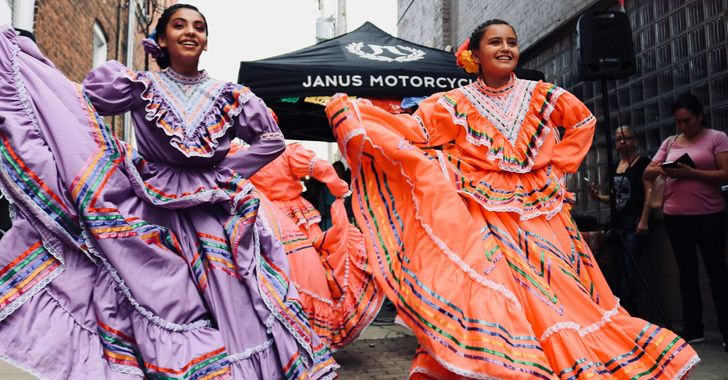

women in street dancing

Photo by

women in street dancing

Photo by  man and woman standing in front of louver door

Photo by

man and woman standing in front of louver door

Photo by  man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by

man in black t-shirt holding coca cola bottle

Photo by  red and white coca cola signage

Photo by

red and white coca cola signage

Photo by  man holding luggage photo

Photo by

man holding luggage photo

Photo by  topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by

topless boy in blue denim jeans riding red bicycle during daytime

Photo by  trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by

trust spelled with wooden letter blocks on a table

Photo by  Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by

Everyone is Welcome signage

Photo by  man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by

man with cap and background with red and pink wall l

Photo by  difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

Photo by

difficult roads lead to beautiful destinations desk decor

Photo by  photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by

photography of woman pointing her finger near an man

Photo by  closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by

closeup photography of woman smiling

Photo by  a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by

a man doing a trick on a skateboard

Photo by  two men

two men  running man on bridge

Photo by

running man on bridge

Photo by  orange white and black bag

Photo by

orange white and black bag

Photo by  girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by

girl sitting on gray rocks

Photo by  assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by

assorted-color painted wall with painting materials

Photo by  three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

three women sitting on brown wooden bench

Photo by

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by

people sitting on chair in front of computer

people sitting on chair in front of computer

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime

all stars lol GIF by Lifetime two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by

two women talking while looking at laptop computerPhoto by  shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by

shallow focus photography of two boys doing wacky facesPhoto by  happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by

happy birthday balloons with happy birthday textPhoto by  itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr

itty-bitty living space." | The Genie shows Aladdin how… | Flickr shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by

shallow focus photography of dog and catPhoto by  yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by

yellow Volkswagen van on roadPhoto by  orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by

orange i have a crush on you neon light signagePhoto by  5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo

5 Tattoos Artist That Will Make You Want A Tattoo woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by

woman biting pencil while sitting on chair in front of computer during daytimePhoto by  a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

a scrabbled wooden block spelling the word prizePhoto by

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion

StableDiffusion